The VagaNile Canal: Women’s Sexuality, Fertility, and Motherhood in Ancient Egypt

By Victoria Semmelhack —————————– Relief from Dendera Temple of Hathor (1500 BCE)

Women’s fertility and birth in ancient Egyptian religion:

In order to understand ancient Egyptian ideas about women’s bodies and fertility, it is necessary to first look at ancient Egyptian religion. Goddesses concerning childbirth, fertility, and motherhood played a significant role in both Egyptian lore and daily life. It is their religious tales and interactions that represented and dictated Egyptians’ real-life understandings of and perspectives on fertility. Nut, the goddess of the sky, is identified most notably by her role as a mother: she is the mother of the stars and of the sun, Re, with one of her foremost duties being to birth Re everyday. She is subsequently identified by her fertility and ability to bear children, also defining her through her connection to men.

From ancient Egyptian religious practices and tales, however, it is clear that a woman’s fertility and creative ability was second to that of a man’s. In Akhenaton’s Hymn to the Aton, Aton, a sun god, is heralded as the giver of life, “plac[ing] seed in a woman and ma[king] the sperm into a person,” and signifying that the ability to actually create new life was attributed primarily to males. Nut, the goddess of the sky and heavens, while she gives birth each day to the sun god, Re, is similarly not involved in the actual process of creating Re. Instead she swallows him whole, and then gives birth to him, making no changes to his form; she simply receives and delivers him. The majority of ancient Egyptian deities concerning fertility are male or androgynous, with none presenting as explicitly feminine. While the Egyptian goddesses Isis and Hathor are perceived by modern historians as related to fertility, this is only within the Western conception of the word, in which fertility also encompasses the nursing and rearing of children. Ancient Egyptian lore and, consequently, ancient Egyptian society, mainly defined fertility by the ability to create new life. Goddesses’ primary responsibilities concerned the encouragement and results of men’s fertility: childbirth and motherhood. In fact, in the Egyptian language, the verb, “to receive” is also used to mean, “to conceive a child,” reflecting the Egyptian understanding of conception in which the man gives a child, fully formed, to a woman, whose primary role is to birth and care for the child. The man is the creative power, the woman the nurturing. This is evident even within Egyptian conceptions of agricultural fertility, an aspect of fertility that was deeply important to Egyptian daily life. The earth and the annual floods that fertilized the soil are male in Egyptian mythology, further indicating the Egyptian belief that fertility was primarily attributed to men.

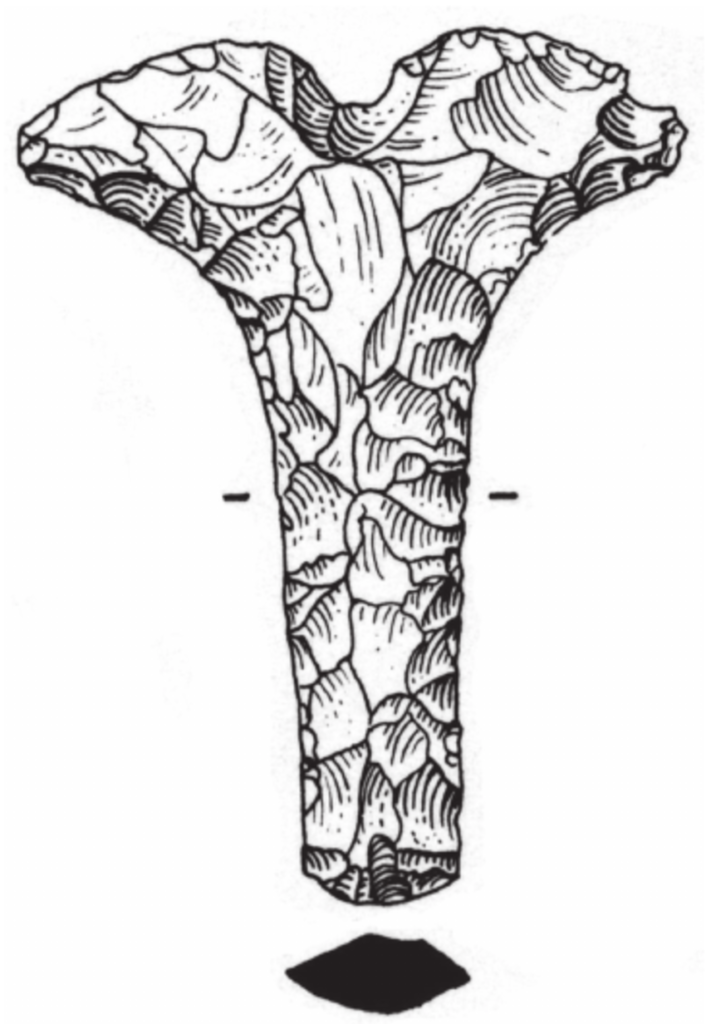

The holy nature of childbirth is additionally exemplified by the similar tools used in both childbirth and in rituals associated with the rebirth of the dead. Pss-kf knives (pictured on the right), used to sever the umbilical cord, and ntrwy blades, used by midwives to clear the lungs of newborns, were also present in the ‘Opening of the Mouth’ ceremony, which guaranteed rebirth in the afterlife.

Pss-kf knife, Middle Kingdom (2030-1650 BCE)

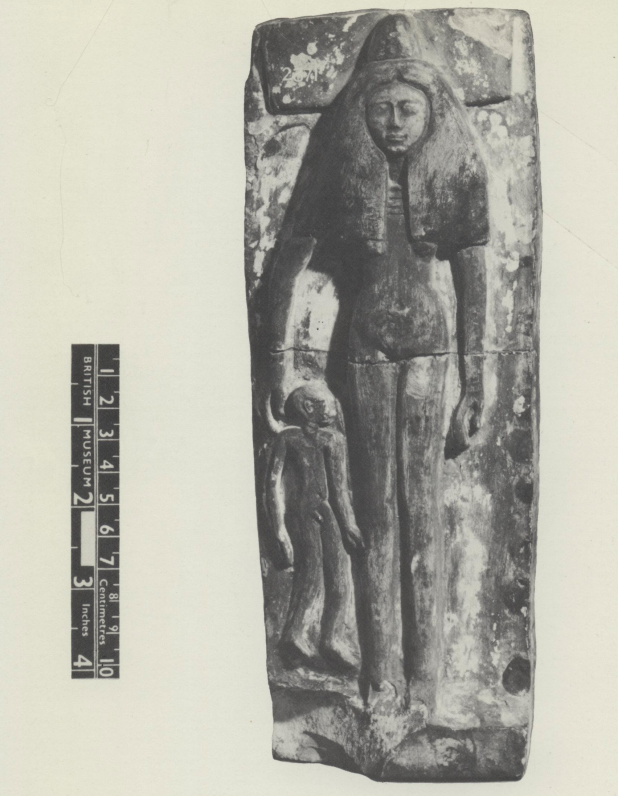

Although depictions of childbirth are rare in ancient Egypt, the Westcar Papyrus exemplifies the religious understanding of childbirth and of goddesses’ involvement in the delivery process: goddesses Isis and Nepthys are pictured supporting Reddjedet during her labor, while the goddess Hathor provided additional aid. There were additionally priests of the royal placenta, and the umbilical cord held particular religious significance, as Horus, in Egyptian mythology, sought his father’s umbilical cord from Seth to bury it with the proper rituals. Three goddesses were primarily concerned with the wellbeing of women both during birth and as mothers: Hathor (see Image A), the protectress of women, Taweret, who is portrayed as a pregnant hippopotamus (see Image B), and Bes (see Image C), who protected the home. Figurines of Bes were frequently given to women in labor, and amulets of Bes and Taweret (as shown in Image B) were often used as protection for pregnant women and mothers.

Image B: Amulet of Taweret (332-30 BCE)

Ancient Egyptian art’s depiction of female sexuality and labor:

Depictions of women in Egyptian art were primarily centered on female sexuality and fertility. A common type of art portraying women is the fertility figurine, whose actual purpose is widely debated. Emerging in the Badarian period (from approximately 4400 to 4000 BCE), fertility figurines, with heavily emphasized sexual organs, were frequently included in tombs. These figurines are particularly visible again in the Middle Kingdom (2030 to 1650 BCE) and New Kingdom (1550-1069 BCE). Some scholars argue that the purpose of these figurines was to provide sexual companionship to men in the afterlife. Other scholars disagree, pointing to the inclusion of fertility figurines in the burials of women that associate them with childbirth and perhaps as connections to Hathor and Isis. An additional interpretation envisions these fertility figurines encompassing both of these roles; with the figurines being generally concerned with the entirety of procreation, from sexual activity to childbirth.

A significant artistic genre of female portrayal was that of the sexualized adolescent, particularly present during the late eighteenth dynasty. Ritual spoons and ring bezels portray young girls nude with large wigs. These wigs were frequently artistically and socially associated with sexuality, particularly in conjunction with the ritual spoon, which symbolized fertility, childbirth, and rebirth. That women’s depictions portray them not only as idealized, but also as sexualized and at an age of prime fertility indicates their role within Egyptian society as receptors of male fertility and as consequently defined primarily through their attractiveness to men. Associations with religious symbols and tools that emphasize childbirth and motherhood additionally denotes their importance in ancient Egyptian societal conceptions of women. The role of women in the creation process as instigators and receptors of men’s fertility is particularly evident through their depictions as primarily young and attractive. It is rare that an Egyptian woman was portrayed as aging, particularly in a society in which a woman’s fertility, and value to society (as we will see later), was dictated by her relations with men; her attraction was therefore of great importance.

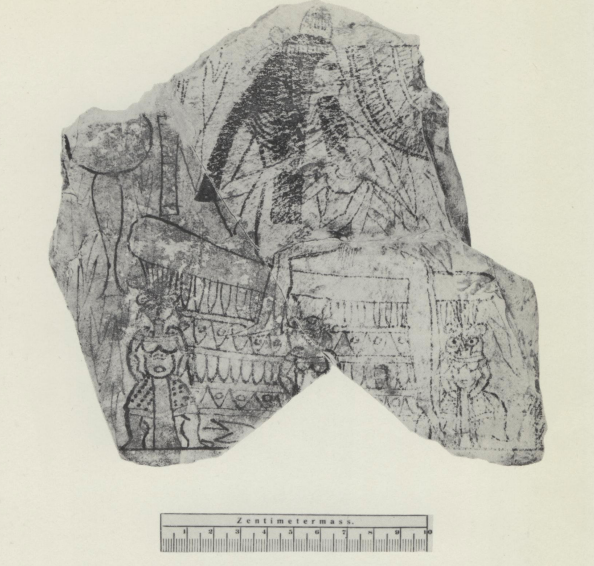

The only consistent representation of pregnancy is that of the goddess Taweret, whose role was to protect pregnant women. An artistic portrayal of women, using flakes of limestone, emerged in the New Kingdom: ostraca. These ostraca occasionally depicted naked women breastfeeding or with children (see Image D). Similar imagery is seen on clay figurines from the same period (see Image E). These figurines were of accompanied by faience amulets, invoking ‘Isis and Horus’, or mother and child imagery, that may have represented the protection of mothers.

A green, steatite figure remains from ancient Egypt that is clearly representative of a midwife. The woman is portrayed with midwifery tools: a pot for oil or salt (with which she might rub the newborn), and an obstetrical instrument used for embryotomies and episiotomies. Figurines such as this might have been carried by midwives to indicate their profession, or might have also been given to laboring mothers for both religious and psychological comfort.

How did art and religion define and represent ancient Egyptian women’s societal roles?

Ancient Egyptian society’s perception and value of women, as indicated by their art and religion, revolved around their assistant role to the fertility of men, as well as their ensuing motherhood. So as to maximize their fertility, Egyptian women were married soon after their menstruation started, and frequently began having children between the ages of twelve and fifteen. In fact, a passage from the Instructions of Ani, implies that marriage was the means through which women became considered adults. Women would be expected to have multiple children, often giving birth every year. Consequently the majority of women had more than five children. Fertility and offspring were of utmost importance to marriages, to such an extent that some men chose to enter a ‘year of eating’, or trial marriage, to determine if a woman was able to have children. A couple’s focus on producing children may explain the presence of fertility figurines in household shrines dedicated to Hathor. Motherhood increased a woman’s status both within her family and in Egyptian society; mothers were highly respected. The primacy of motherhood is indicated by several Egyptian societal conventions, particularly in that a son’s love for his mother was supposed to triumph his love for any other woman. That Egyptian women could gain social mobility by becoming mothers, and that mothers were accorded significant respect, indicates that their reproductive and domestic duties defined the ways in which they were perceived in ancient Egyptian daily life, religion, and art.

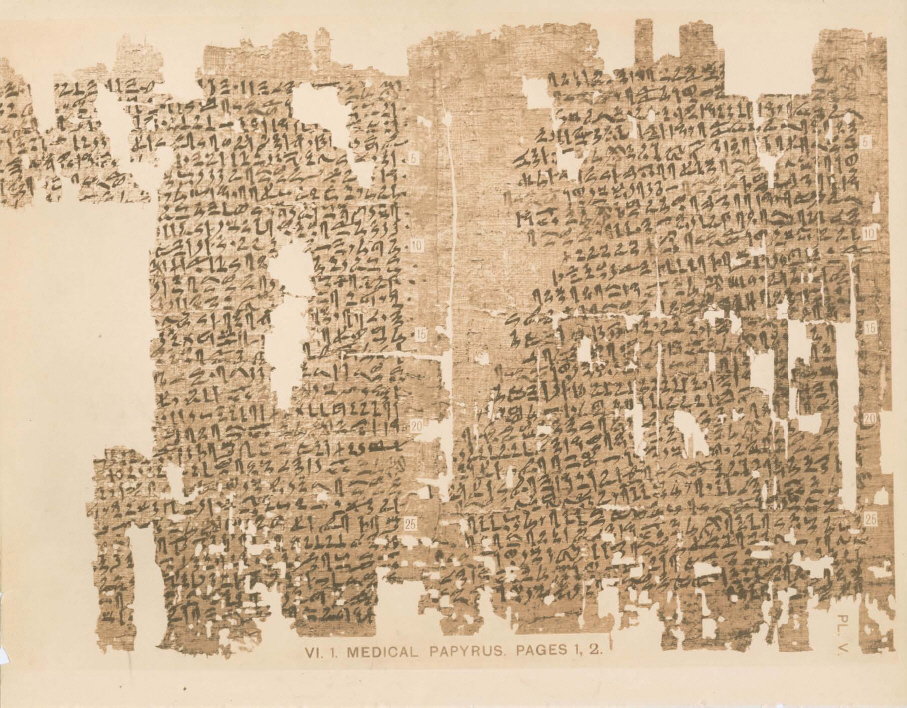

Ancient Egyptian medical understanding of women also emphasized how motherhood was their most significant role. Medical papyri such as the Berlin and Kahun Papyri provided guidance about the proper examinations of women’s breasts in order to determine if they were capable of conceiving. The majority of women’s symptoms were also attributed to their womb, such as one case in which a woman had such a ‘want in her womb’, or desire to have a child, that she became sick. Other nervous disorders were blamed on the womb, particularly on a condition in which the womb moved in a woman’s body. The Kahun Papyrus (pictured on the left, dating from 1800 BCE) describes one woman who was unwell due to a diseased womb. Her womb, according to the papyrus, became sick “because it ha[d] moved.” The focus, even in regards to medicine, on a woman’s reproductive system signifies the extent to which a woman’s reproductive ability was a defining feature of her identity and position in society. The ostraca, figurines, and Turin Papyrus indicate Egyptian interest in women’s sexuality, partly demonstrated as well by the sexualization of women in men’s tombs. In the world of sexuality and fertility, ancient Egyptian women were second to men, both in their roles as seducers and in their primary function to stimulate male procreation.

Kahun Papyrus (1800 BCE)

Gynecology and midwifery in ancient Egypt:

Gynecological practices are documented on a variety of medical papyri. The Kahun Papyrus, written in approximately 1880 BCE, possesses seventeen gynecological entries, as well as an additional seventeen instructions for sterility and pregnancy exams. The Ebers Papyrus also has gynecological information, such as solutions for a prolapsed uterus which, through the examination of mummies, has emerged as a relatively common condition for ancient Egyptian women. Other gynecological maladies discussed in the Ebers Papyrus are contraception, childbirth, and sexually-transmitted diseases. Childbirth and contraceptive practices are additionally detailed in the Berlin Papyrus. From the above papyri, it is evident that women frequently visited doctors for a variety of gynecological and obstetric issues. These doctors, however, do not seem to have been involved in childbirth. Instead, midwives attended labor and delivery.

Midwifery in ancient Egypt was a recognized women’s profession, as indicated by the Temple of Neith at Sais’ school of midwifery. There was an additional religious component to midwifery which accorded it societal importance: the tale, documented in the Westcar Papyrus, of Reddjedet’s labor (as mentioned above), in which she was aided by Isis, Nepthys, Hathor, and the royal midwife Heket, in her birthing of her triplet sons. That the goddesses chose to help with labor accorded the midwives religious esteem. Although the ancient Egyptian language did not possess a word for midwife after the Old Kingdom, midwives likely continued to practice, perhaps more through kinship networks than professional ones. For example, a woman’s midwife might have been her servant, family member, or friend.

Birth itself seems to have occurred in a structure separate from the house, built either in the garden or on the house’s roof; this was likely intended to help separate the mother and infant from the rest of the family and community. The hieroglyphs for “give birth” and “deliver” indicate that early Egyptian women squatted close to the ground in childbirth. Eventually, a brick was placed under each foot of a laboring woman (as pictured below). The bricks evolved into a mshnt, or confinement chair, in approximately 2500 BCE (pictured to the left, in a relief from the Temple of Kom Ombo: 332-30 BCE). These chairs were likely made of brick or wood, and consisted of a seat with a semi-circular hole and two wooden rods attached to each edge to support the laboring woman.

An overarching question emerges from this article: how were women perceived in ancient Egyptian society? Their maturity was defined by the age at which they were deemed marriageable and, by extension, able to conceive. The duty for which they were prized and could gain status was that of becoming a mother. Medical knowledge of women’s bodies revolved around their wombs. Artistic depictions of women emphasized their attractiveness to, and stimulation of, men, consequently alluding to their eventual pregnancy. Within Egyptian mythology, goddesses’ duties frequently related to fertility, childbirth, and motherhood. Childbirth itself was a primarily female affair, attended to by female midwives and occurring in isolation from the rest of the household and society. The image that emerges of an ancient Egyptian woman is one that revolves around all aspects of childbirth and motherhood, placing the value of a woman ultimately upon her relations with, and making her secondary to, men, particularly in that men were accredited with the actual creative power.

Relief of a laboring woman on a confinement chair (Temple of Kom Ombo: 332-30 BCE)

Works referenced:

Audouit, Clémentine. “Women’s Intimacy: Blood, Milk, and Women’s Conditions in the Gynecological Papyri of Ancient Egypt.” In Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and Autonomy, edited by Mariam F. Ayad, 381–94. The American University in Cairo Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2r4kwrg.26.

Graves-Brown, Carolyn. 2010. Dancing for Hathor : Women in Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Accessed November 15, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Hollis, Susan Tower. “Women of Ancient Egypt and the Sky Goddess Nut.” The Journal of American Folklore 100, no. 398 (1987): 496–503. https://doi.org/10.2307/540908.

Pinch, Geraldine. “Childbirth and Female Figurines at Deir El-Medina and El-‛Amarna.” Orientalia 52, no. 3 (1983): 405–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43077567.

Rand, H. “Figure-Vases in Ancient Egypt and Hebrew Midwives.” Israel Exploration Journal 20, no. 3/4 (1970): 209–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27925235.

Robins, Gay. Women in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Roth, Ann Macy. “Father Earth, Mother Sky.” In Reading the Body, edited by Alison E. Rautman, 187-201. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.

Sweeney, Deborah. “Forever Young? The Representation of Older and Ageing Women in Ancient Egyptian Art.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 41 (2004): 67–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/20297188.

University College London. “Gender: sex and fertility – non-royal evidence.” Digital Egypt for Universities. Last modified 2002. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/gender/sex.html.

Watterson, Barbara. Women in Ancient Egypt. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Williamson, Jacquelyn. “Alone before the God: Gender, Status, and Nefertiti’s Image.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 51 (2015): 179–92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26580635.