By Ryan Flanagan: Classics 220, Professor Jordan Rogers

Money as Symbol

When was the last time you used a form of money to pay for something? Chances are it was pretty recent. Today, many payment systems have been digitized, either taking place through credit card payments, where transactions are recorded on an electronic ledger, or through other newly emerging digital mediums including PayPal, Venmo, CashApp, and even Bitcoin.

But forget about these modern forms of payment for the moment and think about the last time you used a physical form of currency, such as a dollar bill or a silver quarter. What iconography was represented on that dollar bill or quarter, and what do you think that iconography was meant to convey?

If you are an American, the chances are solid you have used a quarter recently to pay for a parking meter, or for a shopping cart at your local grocery store. In the United States, all quarters famously contain a profile image of President George Washington on the ‘heads’ side, with the ‘tails’ side commonly containing the insignia of a spread-winged eagle. In some instances, the ‘tails’ side of a quarter contains insignia portraying a variety of national parks, historical individual figures, and other things of national importance. A 2001 edition coin representing the state of New York, for example, portrays an image of the Statue of Liberty: a gesture to the American values of liberty and opportunity.

Alexander’s Coins

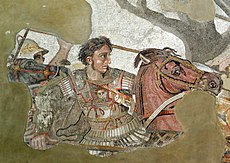

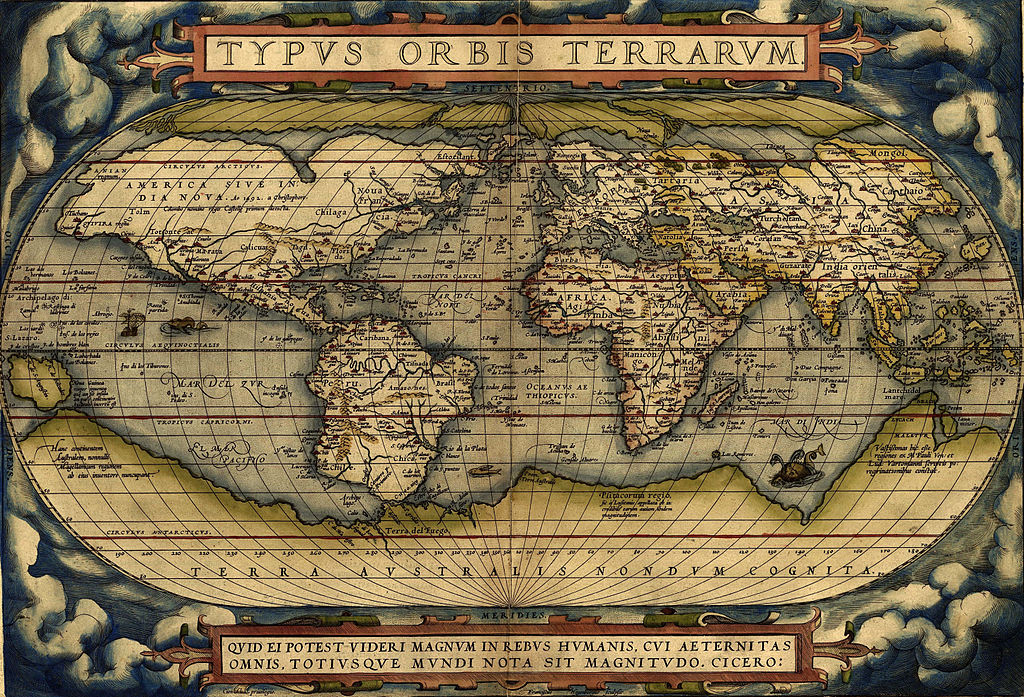

Now that you have completed this exercise of considering what is represented on contemporary physical forms of monetary exchange, the following webpage is designed to travel back in time to the era of the Macedonian Empire (808-168 BCE). Perhaps you have heard of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), the military conqueror who expanded the Macedonian empire to record heights, and who expanded Greek influence and control into the region surrounding the Nile River valley in North Africa as early as 332 BCE.

By no means did Alexander the Great invent physical currency. In fact, Herodotus wrote about the Lydians originating silver and gold coins around 600 BCE, while the Athenians distributed silver coins emblazoned with the ‘Athenian owl’ during the era of Athenian and Theban dominance of Greece prior to the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE. Upon Philip II’s victory in this decisive battle, Alexander’s father Phillip II issued coins inscribed with his own image. When Alexander inherited his father’s empire and took control of the royal mint in Tarsus in 333 BCE during his Asia campaign, he began to issue coins with his own inscription.

As the Macedonian Empire grew massively under Alexander’s military command, his insignia became more associated with his dominance and the divine nature of his rule, which Alexander sought to reinforce through depictions of himself which were closely intertwined with important Greek deities.

A prime example of this is the coin depicted below: one side of which portrays Alexander as a young Heracles, the Greek divine hero. On the flip side of this coin, a bare chested image of Zeus appears seated on a throne, meant to reinforce that Alexander was descended from the most important Greek deity.

Two flip-sides of a coin; the furthest to the left depicting Alexander as Heracles and the furthest to the right depicting Zeus. Photo Courtesy of the University of Canterbury

Coins such as the one pictured above served not only the ideological purpose of reinforcing Alexander’s power, but also the practical purpose of serving as a medium of exchange. Practically, coins issued under Alexander’s rule served the purpose of paying mercenary soldiers across the Macedonian empire, who outnumbered conscripts and soldiers provided from Macedonian allies by a ratio of 3:2. (Meadows, “The Spread of Coins in the Hellenistic World, 171) As such, the enduring security of the Macedonian empire was dependent on coins, which placated mercenaries into good behavior by providing them with purchasing power and the hopes they could one day purchase land.

Introducing Greek Coins to Egypt

In 332 BCE, the indigenous people of Egypt welcomed Alexander the Great and his army, who liberated the Nile River Valley from Persian control after defeating the Persians in Syria and the Levant. Upon arriving in Egypt, Alexander established the city of Alexandria on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and journeyed westward into Libya. In Libya, Alexander arrived at the Oasis of Siwa, where he symbolically visited the oracle of Ammon, constructed in the fifth century BCE by the Egyptian Pharaoh Amasis. Alexander’s visit to the oracle can be perceived as a deliberate maneuver to prove his direct lineage to Ammon, the most powerful of the Egyptian deities. As legend goes, when Alexander arrived at the oracle of Ammon in Siwa, he was greeted as Ammon’s son.

Consistent with his conquest of territory in what is now the modern day Middle-East and Western Asia, Alexander brought with him an army of mercenaries who occupied Egypt. To pay his soldiers, Alexander established a mint in Memphis and began producing silver coins. When Alexander died in 323 BCE and control of Egypt was passed on to Alexander’s companion Ptolemy of Soter, Greek mercenaries remained in Egypt and the need for silver coins to pay them continued.

While Egypt continued to be controlled by the Ptolemies between 305 and 30 BCE, a unique monetary system was established due to geographic limitations and unique cultural circumstances. As for the former, the absence of naturally occurring silver ore in the Nile River valley led to a reduction in the concentration of silver in Ptolemaic coins relative to standard Macedonian coins. (Milne, “Ptolemaic Coinage in Egypt, 151)” Meanwhile, as Egyptian culture interacted with Greek culture, the iconography of Ptolemaic coins began to reflect Egyptian cultural values.

How do Ptolemaic Coins Reflect the Concept of Cultural Hybridity?

According to the Sage Reference Library, cultural hybridity constitutes the “effort to maintain a balance among practices, values, and customs of two or more cultures.” The concept of cultural hybridity was popularized by Homi Bhabha, who focused on the use of hybridity (i.e. the mixing of cultures) as a subversive tool employed by colonized peoples to challenge oppression from their colonizers. (Bhabha, “Signs Taken for Wonders”) An examination of Ptolemaic coins provides an interesting method through which to examine Egyptian cultural values mixed with Greek traditions and customs. As has already been discussed, Alexander’s conquest of Egypt facilitated the spread of coinage into Nile River valley as it became necessary to use coins as a means of paying mercenary soldiers.

However, despite the introduction of coins into Egypt around 330 BCE, payment-in-kind continued to be the main form of exchange utilized in Ptolemaic Egypt through 119 BCE: a phenomenon proven through documentary evidence of payments occurring in commodities like lentils, beans and seeds. Thus, coins in Ptolemaic Egypt were used primarily to pay Greek mercenaries, and as a result Ptolemaic coins were more likely to be held by ethnic Greeks than native Egyptians. Interestingly enough, despite evidence which suggests coins were not commonly used as a form of payment among native Egyptians themselves, the iconography of Ptolemaic coins reflected Egyptian cultural values to a significant extent. As the remainder of this page will showcase, Ptolemaic coins drew on the distinctively Egyptian cultural values of religion, legitimacy, and gender equality.

The Portrayal of Alexander as Amon

Similar to the manner in which Alexander utilized traditional Macedonian coinage to portray himself as a divine leader through connections to the traditional Greek deities of Heracles and Zeus, the Ptolemies distributed coins which portrayed Alexander with the horns of Ammon on his head: a distinct feature associated with Egypt’s chief deity. Ultimately, this iconography should be seen in the context of Alexander’s famous visit to Siwa, which reinforced his direct lineage to Ammon.

Since the Greeks understood Ammon to be the equivalent of Zeus, the issuance of Ptolemaic coinage depicting Alexander adorned with the horns of Ammon did not present a fundamental re-understanding of Alexander’s identity. Instead, depicting Alexander as Ammon resembled a unique moment where Alexander’s legitimacy as a divine ruler could be communicated in an Egyptian context. Ultimately, the portrayal of Alexander as Ammon on Ptolemaic coinage can be perceived as an effort undertaken by the Ptolemies to reinforce the legitimacy of Greek Macedonian rule over Egypt in a manner which drew from Egyptian religious symbolism.

The Portrayal of Incest

Another interesting Ptolemaic coin is the gold piece showcasing Ptolemy II: the son of Ptolemy Soter (“The Savior”) and the second ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt. The defining feature of this coin is its representation of Arsinoe II as another figure alongside Ptolemy II on the front side of the coin. Arsinoe II was famously Ptolemy II’s sister, and their marriage to one another was against traditional Greek custom which frowned upon incestuous marriage. Nevertheless, Ptolemy II’s marriage to Arsinoe II set a precedent of intermarriage to follow among the ruling family in Ptolemaic Egypt.

The overt portrayal of Ptolemy II alongside Arsinoe suggests the idea that Ptolemy II’s marriage to his sister Arsinoe was celebrated, and even seen as a symbol of legitimacy in Ptolemaic Egypt. The emergence of incestuous marriages within the Ptolemaic ruling family can be perceived as a trend which emanate out of the historical context of incestuous marriages in Pharaonic Egypt, where it was common for intermarriage to occur within the Egyptian royal family. In this vein, the coin of Ptolemy II is an exceptional example of cultural hybridization in Ptolemaic Egypt, where it can be perceived that the Ptolemaic ruling family borrowed from Egyptian social norms of intermarriage in order to adhere to local expectations and ensure legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

The Portrayal of Gender Equality

Finally, the portrayal of Cleopatra VII on a Ptolemaic coin serves as an example of how the historical context of gender roles in Pharaonic Egypt informed an understanding of gender in Ptolemaic Egypt. Unlike in Macedonian Greece, where gender roles were rigid and characterized by a carefully structured patriarchal society, women in Pharaonic Egypt enjoyed a high degree of freedoms, including the right to sue and obtain contracts incorporating lawful settlements such as marriage and property. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for women in Pharaonic Egypt to assume positions of power, including the position of Pharaoh itself. (Khalil et al., “How Knowledge of Ancient Egyptian Women can Influence Today’s Gender Roles: Does History Matter in Gender Psychology?”)

Thus, in another example of hybridity, the above coin inscribed with an image of Cleopatra VII speaks to the power of Pharaonic Egypt’s historical context of gender equality, which informed a more liberal understanding of gender roles from the Ptolemaic perspective.

Conclusion

In summary, the portrayal of distinct Pharaonic conceptions of religion, legitimacy, and gender roles through Ptolemaic coins is a testament to the cultural hybridization which occurred in Ptolemaic Egypt in the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Nile River Valley. What is remarkable about these coins is that they did not necessarily have to reflect Egyptian cultural norms to the extent they did considering the likelihood that Ptolemaic coins were used almost exclusively to pay soldiers, while the Egyptian people in general continued to resort to payment-in-kind to settle transactions.

Nevertheless, the distinct culture of Pharaonic Egypt significantly shaped the design of Ptolemaic coins. Ultimately, this is perhaps reflective of the willingness of the native Egyptian population to push against the dominant Greek culture enforced upon them via colonization, just as much as it is reflective of the Macedonian Greek desire to embrace the new cultural values which were introduced to them through their interactions with Egyptian subjects.

Works Cited:

Bhabha, Homi K. “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority Under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817. ” University of Chicago Press Critical Inquiry vol. 12 (1985): 144-165.

Meadows, Andrew. “The Spread of Coins in the Hellenistic World.” Explaining Monetary and Financial Innovation (2014): 169-95.

Milne, J.G. “Ptolemaic Coinage in Egypt.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 15 no. 4 (1929): 150-153.

Khalil, Radwa, et al. “How Knowledge of Ancient Egyptian Women Can Influence Today’s Gender Roles: Does History Matter in Gender Psychology.” Frontiers in Psychology (2017): 1-7.