Alexander the Great, Egypt, and Divine Rule

by Henry Petrini

Alexander the Great riding Bucephalus, his horse, from the Alexander Mosaic. Naples Archaeological Museum.

Alexander the Great: military leader, conqueror, … god? Alexander is credited with rapidly spreading the borders, culture, and administration of Hellenistic Greece during a reign of only 13 years throughout Northern Africa, Asia Minor, and the Mediterranean. Alexander’s influence in Egypt was transformative and far-reaching, providing a unique basis for the rulership of his successors. Elements of his rulership and legacy, such as the posthumous Cult of Alexander in Alexandria, offer fascinating insights into the overlap between Greek and Egyptian identity in this period. Other facets of culture from Ptolemaic Egypt, such as coinage and busts, also allow for an examination of how Alexander’s legacy shaped rulership and traditions to come, and how Egyptian populations were treated as colonial subjects of Hellenistic government.

Alexander the Great & Ptolemaic Egypt

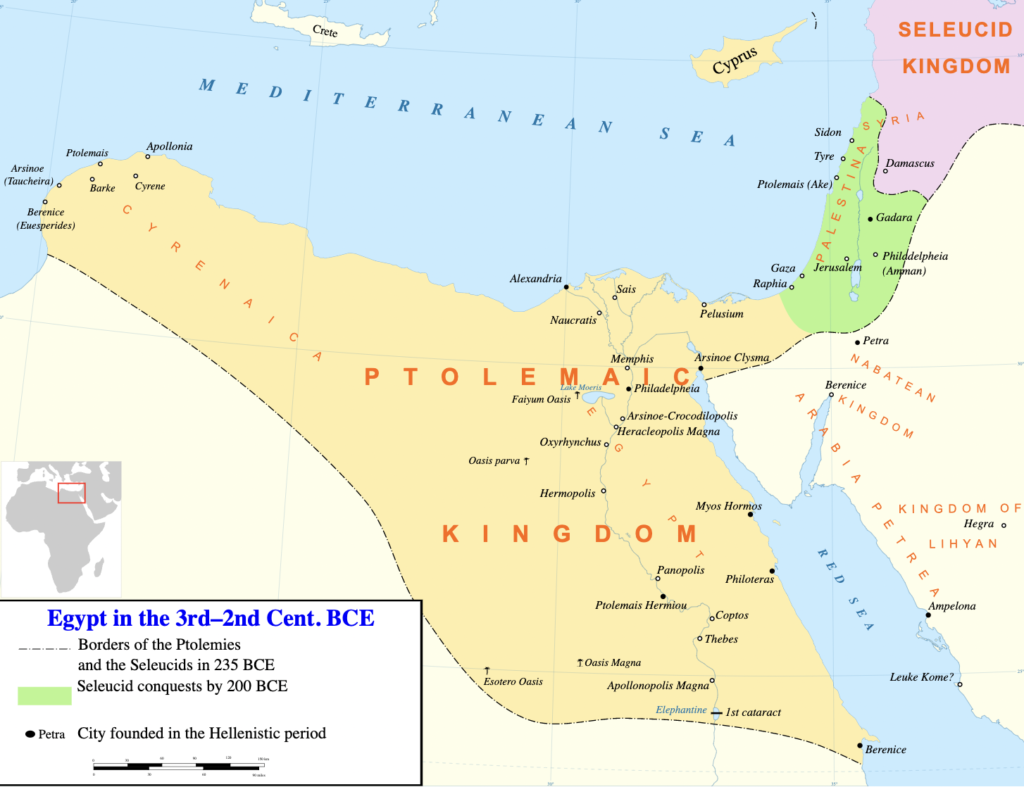

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great invaded Egypt while it was ruled by the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The Persians’ oppressive rule over the Egyptian population meant that many Egyptians looked to Alexander and his army as saviors. Alexander’s army took Egypt from the Persians and split the land between various generals, cementing Greek control over Egypt. Alexander founded Alexandria, an Egyptian city that became a focal point for Hellenistic culture in North Africa and the Mediterranean at large.

After Alexander’s death, his top generals fought over control of the empire during a wide-scale battle known as the Wars of the Diadochi. One of his generals, Ptolemy I, gained control over Egypt. Ptolemy I, a Macedonian, eventually gained the title of Pharaoh in Egypt. Egypt is referred to as ‘Ptolemaic Egypt’ during this period and is distinguished by Greece’s presence as an occupying power as well as its use of Egyptian cultural imagery and practice to gain legitimacy in the eyes of its subjects. Occupying Greek forces in Ptolemaic Egypt introduced currency in the form of coinage to Egypt, whereas before Greek occupation, the Egyptian economy was largely based on agriculture and trade. These coins allowed for Greek and Egyptian infrastructure and economy to blend more smoothly, and they also acted as a form of propaganda.

Social and economic stratification were large parts of daily life, placing Greeks and Macedonians above native Egyptians in practically every facet of life until the later Ptolemaic Dynasty. Greek, for example, became the official administrative language of Ptolemaic Egypt, introducing a language barrier between many Egyptians and high-ranking governmental jobs. Civil unrest was frequent and evidence of organized protest and unrest can be seen throughout Ptolemaic Egypt, the most blatant form of which was the creation of an independent Pharaonic state by Native Egyptians in the late 2nd century BCE.

The Cult of Alexander the Great

This period rarely saw the true integration of Greek and Egyptian cultures, as most Greeks were regarded as privileged members of society and did not mix with Egyptians. Despite these differences and separations between cultures, Alexander’s impact offers a chance to explore the overlap between cultural traditions, such as the Greek practice of the founder cult, or founding myth, and its influence on Ptolemaic ruler cults, creating a blend of “Egyptian tradition and Greek initiative.”

The Ptolemaic tradition of ruler cult, whereby a ruler is posthumously labeled a god, stems from an integral tradition in indigenous Ancient Egyptian society: the idea that rulers – kings, and queens alike – are divine. Ancient Egypt’s Pharaohs were seen as gods and intermediaries between humans and members of the Egyptian pantheon. Pharaohs maintained ma’at – an Ancient Egyptian term that means “cosmic balance”.4 The blurring of the boundaries between the mortal and immortal worlds was an essential aspect of Egyptian leadership. This was practically unheard of in Ancient Greek society until Alexander the Great demanded his subjects worship him after his exposure to the tradition in Egypt. After Alexander’s conquest of Egypt, he was declared the son of Amun, the chief Egyptian god, by an Oracle in the Libyan desert – a powerful development in the cultural overlap between Egyptians and Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt. This effectively allowed Alexander to cement his place as a member of the Egyptian divine ranks.

In contrast to the true deification of leaders in the Ancient Egyptian world, Ancient Greeks had a tradition called the founding myth, or founder cult. The oikistes, or founder, of a Greek city, was given the responsibility of choosing a location for settlement and directing the efforts of early colonists. After the death of an oikistes, a cult would arise dedicated to him. This cult, however, was distinctly non-divine and existed to cement the authority of the founder of a city and promote him to a legendary status instead of deifying him.

The Cult of Alexander, then, presents an interesting union between the Greek founding cult and Egyptian Pharaonic tradition. Alexander stands out as a Greek leader whose accomplishments have warranted special recognition, and whose ties to, and association with, Egyptian society, have elevated him to a divine status. When Diodorus Siculus, an Ancient Greek historian, describes his funeral, he writes:

“Because of [the carriage’s] widespread fame it drew together many spectators; for from every city into which it came the whole people went forth to meet it and again escorted it on its way out, not becoming sated with the pleasure of beholding it.”

– Diodorus Siculus, Book XVIII

Alt Text: A 19th-century depiction of Alexander’s funeral procession.

If this account is to be believed, it speaks to the adoration and reverence that followed Alexander even in death, and across his Empire. At the same time, it is important to consider who Diodorus would have been writing for: if his audience were Greek, it would be important for them to see support and love for Alexander. Regardless of the historical accuracy of this account, it speaks to the high esteem the Greeks held Alexander in, undoubtedly due to the ethnic associations between them. As will be discussed later, there are very few official accounts of Egyptian attitudes toward the Ptolemies that exist today. The vast majority of Greek sources that today’s historians are able to access feature practically no insight into dialogues between Greek and Egyptian characters and identity, either. This ties into a fundamental issue that lies at the center of Ptolemaic Egypt: the near-invisible presence of Egyptians in historical records, which will be explored below. Alexander’s far-reaching impact as a Greek in Ptolemaic society is significant, as it places a Macedonian Greek in a Pharaonic position, which is a uniquely Egyptian tradition. The prioritization of Greeks over Egyptians is a common theme in Ptolemaic Egypt, reaching far beyond the time of Alexander himself.

Ptolemy I Soter

Alexander’s influence as a figurehead of Ptolemaic Egypt far outstretched the immediate period after his death, and his impact defined the beliefs and actions of the future rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt. The divinity with which he was associated became the model for Ptolemy I and his successors. It’s hard to understate the importance that Alexander held to Ptolemy I as an ally: during Alexander’s funeral procession through Egypt, Ptolemy I went so far as to steal his body and bring it to Memphis, a city in Ptolemaic Egypt. Ptolemy I also used his collaboration with Alexander to legitimize his own claim to divine rulership. After all, what better way is there to cement yourself as a god than to have been the friend of, and military advisor to, an important one?

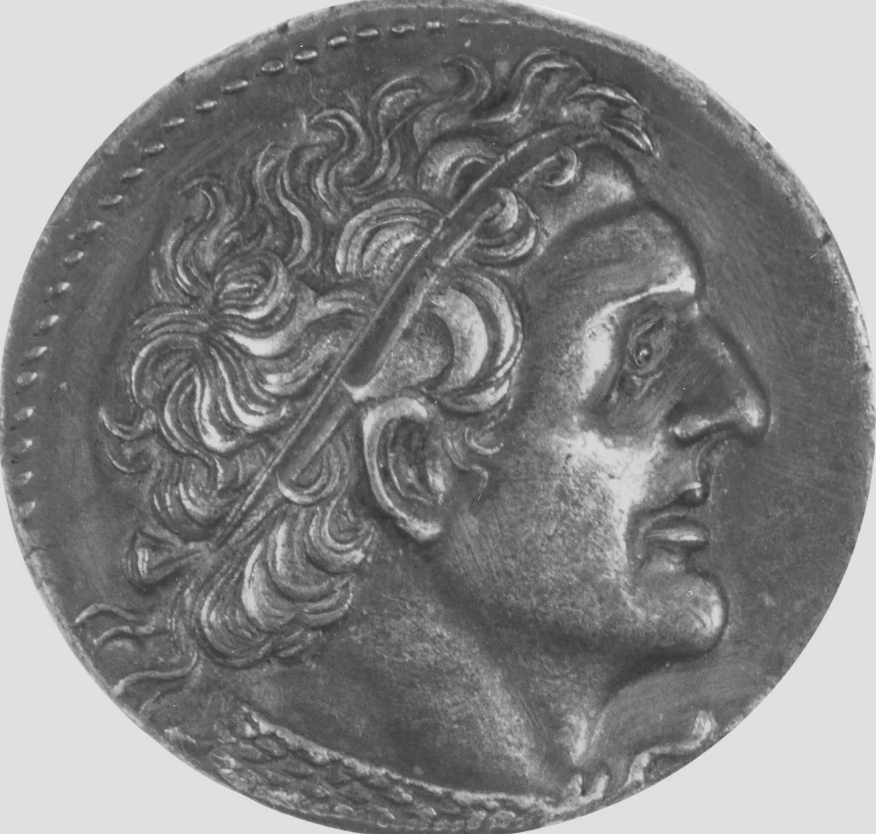

The different facets of Ptolemy’s public identity echo those of Alexander while being more explicitly associated with Egyptian tradition. While on coinage (right) he can be seen donning Greek clothing such as the tainia, in busts he becomes a bonafide Pharaoh (left). The Identity of Ptolemy I was created and crafted so that his Egyptian and Greek subjects would be able to recognize him through common cultural imagery. In adopting Egyptian tradition, the Ptolemies attempted to gain legitimacy in the eyes of their native Egyptian subjects. He was eventually referred to as “Ptolemy I Soter”, roughly translating to “Ptolemy the Savior.”

During the rule of Ptolemy I, the chief priest at Alexander’s tomb was the highest religious office in Ptolemaic Egypt, barring that of the Pharaoh. In fact, years and dates used in official documents were named after each priest, highlighting their importance to government bookkeeping and positions of high office. The framing of governmental documents in reference to priests and religious officials not only indicates the Egyptian tradition of the union of church and state but also ties that union directly to the legacy of Alexander the Great. Over the course of the Reign of the Ptolemies, until the end of the reign of Ptolemy VIII, there were likely 175 priests employed as priests of Alexander, indicating the importance and longevity of the position.

Ptolemy II & The Cult of the Ptolemies

While Ptolemy I’s reign gained credibility largely through an appeal to divine authority in Alexander the Great, it was not until after Ptolemy I’s death that he himself became a god in the eyes of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Ptolemy II, the successor to and son of Ptolemy I, drew inspiration from the posthumous cult of Alexander and designated his father and mother as gods after their deaths in 283-282 BCE. Specifically, they were designated as theoi sōtēres, meaning savior gods. This had huge effects on the rest of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. This political move not only reinforced the use of Egyptian cultural values in Ptolemaic leadership through religious reverence but also expanded the cult of Alexander the Great to include the Ptolemies.

Ptolemy II continued to develop the infrastructure of the Cult of Alexander, creating different religious positions that became subordinate priests to the priest of Alexander, the highest religious office in Ptolemaic Egypt. Ptolemy II also wasted no time labeling himself a divine ruler in order to secure his position as a Ptolemaic ruler in the vein of his father, Ptolemy I, and Alexander the Great. He labeled his sister-wife Arsinoe II and himself theoi adelphoi, or brother gods, securing himself a spot as a divine ruler of Egypt.

Egyptians in Ptolemaic Egypt

While native Egyptian culture provided the basis for divine rulership in Ptolemaic Egypt and helped legitimize the rule of the Ptolemies, Egyptians themselves were considered inferior to the Greeks. The court poetry of Theocritus, a poet from Ancient Greece, serves as a valuable tool to examine what the elites of Ptolemaic Egypt thought of Egyptians and Ptolemaic divinity:

A bust of Ptolemy II featuring Pharaonic headdress.“You have accomplished many good deeds, Ptolemy,

– Theocritus, Idyll 15, 215.

since your father took his place among the immortals; no evildoer

sneaks up to someone on the street, Egyptian style, and hurts him,

doing tricks that men forged from deceit used to play,

each rascal as bad as the other, wicked pranksters, curse them all.”

In the same breath that Theocritus venerates the rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt, a Greek-occupied institution, he diminishes the humanity of its native Egyptian inhabitants. The “Egyptian style,” according to this excerpt, is one of thievery and violence. According to Theocritus, this suppression of the mischievous Egyptian spirit is due to the rulership of Ptolemy I Soter. The divinity of the Ptolemies is used as a tool to exclude Egyptians from an ordered society, despite the Egyptian roots of Ptolemy’s divinity. Idyll 15, a “depressingly brief and one-sided” moment of discourse, is an uncommonly vocal piece of literature concerning Greco-Egyptian relations (McCoskey, 15). There are very few literary records that detail Egyptian status, or even Greco-Egyptian interactions, within Ptolemaic Egypt, an indicator of Egyptian’s absence in elite circles as well as the lack of thought afforded to them in Greek memory.

In another facet of Ptolemaic culture that is overtly concerned with preserving Greek identity (coinage), distinctions between Greek and Egyptian members of the Ptolemaic Kingdom are made clear. Over the course of the rule of the Ptolemies, the subjugation of Egyptians, or at least the perceived superiority of Hellenistic culture, is obvious. In even early instances of coinage, Greek symbolism is omnipresent. In one coin, Athena wears a Greek headdress (left). In another, Ptolemy I, leader of Ptolemaic Egypt, wears Greek clothing (above). In later iterations of coinage, the Ptolemies tended to distance themselves from explicit associations with imagery associated with Alexander, yet their Greek influences remained. The choice to put these images on coinage that would be spread throughout Ptolemaic Egypt is not insignificant – it could have served as a reminder to the native Egyptian population that it was the Greeks who were truly in control.

So What?

The fabric of Ptolemaic Egyptian society was influenced by many factors, chiefly the influence of Hellenistic culture as a colonial occupying power. The first instance of Greek rule in Egypt, beginning with Alexander the Great, led to the worship of the Ptolemies, and set a precedent of Greek rulers unifying cultural imagery to gain the favor of as many of their subjects as possible. Conflict exists between the Egyptian traditions adopted by Ptolemaic rulers and the inability of those rulers to affirm the humanity of their Egyptian subjects. The colonial legacy of Greece has been long ignored and forgotten by historians, but in examining it, a more complete picture of Ptolemaic Egypt emerges. The history of Ptolemaic Egypt is complex – it juggles colonial occupation and competing cultural traditions, making it a fascinating place that allows for the examination of Northern African Identity in the presence of Hellenistic colonialism.

Works Cited

Bosworth, A. B. Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Archive.org. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2008. https://archive.org/details/conquestempire00abbo/page/70/mode/2up?q=oracle.

Heinen, H.. “Ptolemy II Philadelphus.” Encyclopedia Britannica, November 5, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ptolemy-II-Philadelphus.

Mccoskey, D. E. (2002). Race Before “Whiteness”: Studying Identity in Ptolemaic Egypt. Critical Sociology, 28(1–2), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205020280010401

Rowell, Sheila. “The Alexander Cult and Ptolemaic Ruler Worship.” Ancient History Resources for Teachers 19, no. 2 (1989): 82. http://ezproxy.carleton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/alexander-cult-ptolemaic-ruler-worship/docview/1293400866/se-2.

Siculus, Diodorus. “(Book XVIII, Continued).” LacusCurtius • Diodorus Siculus – Book XVIII Chapters 26‑47. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/diodorus_siculus/18b*.html.

Theocritus. Idyll 15. Loeb Classical Library. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://www.loebclassics.com/view/theocritus-poems_i-xxx/2015/pb_LCL028.215.xml.

Werner, R.. “Ptolemy I Soter.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 3, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ptolemy-I-Soter.