The Intersectionality of Ethnicity and Gender In the Ancient Egyptian World

By Faith Agboola

Introduction

Ancient Egypt was a place where a variety of cultures mixed and adopted each other’s customs. At times, these cultures would be put on display, and some could see it as mimicry, while others could see it as hybridity. At other times, these markers of identity might collide at a point known as the Middle Ground. We should be aware of mimicry, hybridity, and the Middle Ground as we have learned them throughout our term. We have also discussed in our class the concepts of race and ethnicity and how they have played a role in how we view these societies and how others view them. On the other hand, one concept that has yet to be fully explored in ancient Egypt in terms of identity is intersectionality. Intersectionality is the concept that social identities operate on multiple levels, creating unique experiences and barriers for each individual. As a result, oppression cannot be reduced to a single aspect of an individual’s identity; each oppression is dependent on and shapes the other. This translates well into the role of women in ancient Egypt. Intersectionality can help us understand and answer questions like, “How did women in ancient Egypt deal with grappling with multiple identities?” “Did women during this time ever get misidentified due to their ethnographic makeup, and how did it affect their womanhood and how they were perceived?” “Did intersectionality help or hinder the status of some women more than others?” These questions are all thoughtful in the way that intersectionality can be looked at in the context of the role of womanhood in ancient Egypt. This essay will aim to explore and analyze aspects of intersectionality in the context of women in ancient Egypt. This will be accomplished by utilizing a variety of sources, such as papyrological evidence, ethnographic evidence, and firsthand accounts, to provide us with an understanding of how the concept of intersectionality might have impacted the lives of women in Ancient Egypt.

What is Ethnicity?

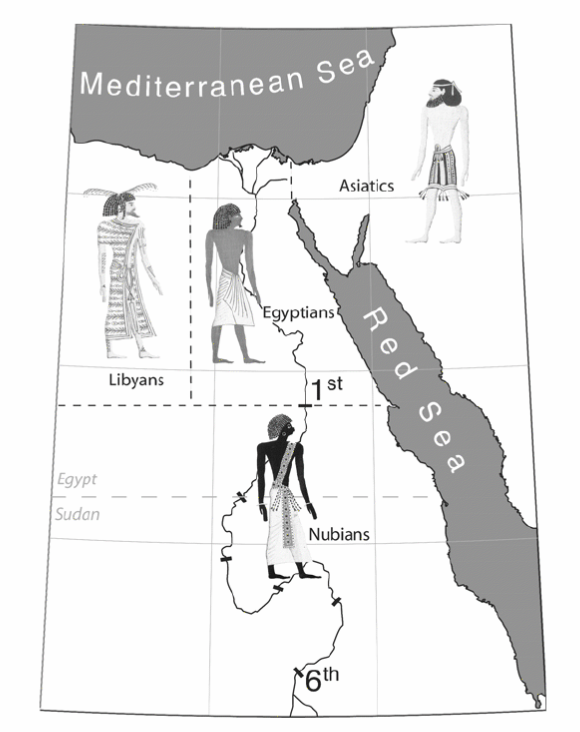

First, it is important to note the working definition of ethnicity that will be used as a basis for this paper. Ethnicity can be defined as a group identity shaped according to changing needs and contexts that most frequently reflects a form of self-grouping or identification of others based on a belief in shared characteristics that may include cultural practices, geography, and/or a notion of imagined shared descent or kinship (Kennedy, 2021). Race is a modern, westernized term that cannot be applied to an ancient civilization due to its lack of relevance, which is why ethnicity is used here instead of race. Understanding how intersectionality enters at all parts of your identity, not just your racial class, is made much easier by taking an ethnic perspective. After defining ethnicity formally, it is crucial to examine examples of ancient historians’ and Egyptians’ own descriptions of their own ethnicity and what it meant to them. For example, Cheikh Anta Diop describes Ancient Egypyt as a “Negro civilization” in his novel The African Origin of a Civilization: Myth or Reality. He continues to state that classic historians cannot continue to write about ancient Egypt while eradicating the idea that Egypt was indeed a part of the history of Black Africa (Diop & Selections., 1974). Furthermore, Diop states that Egyptians were Negroes and that the essentiality of their ethnicity was to be counted amongst those in the Black World. Diop asserts this claim because he recognizes that to analyze other aspects of identity that encompass one’s ethnicity, like language and institutions, we must first understand the origins of one’s ethnicity, which is that Egyptians were Black, Negroes, and African.

Egyptian Notions of Ethnicity

Instruction for King Merikare (2075-2040 BCE):

“Lo the miserable Asiatic, He is wretched because of the place he’s in: Short of water, bare of wood, Its paths are many and painful because of mountains. He does not dwell in one place, Food propels his legs, He fights since the time of Horus, Not conquering nor being conquered, He does not announce the day of combat, Like a thief who darts about a group.”

Instruction of Ani (1336-1279 BCE):

“There’s nothing [superfluous in] our words, Which you say should be reduced. The fighting bull who kills in the stable, He forgets and abandons the arena; He conquers his nature, Remembers what he’s learned … The monkey carries the stick, Though its mother did not carry it. The goose returns from the pond, When one comes to shut it in the yard. One teaches the Nubian to speak Egyptian, The Syrian and other strangers too. Say: “I shall do like all the beasts,” Listen and learn what they do.

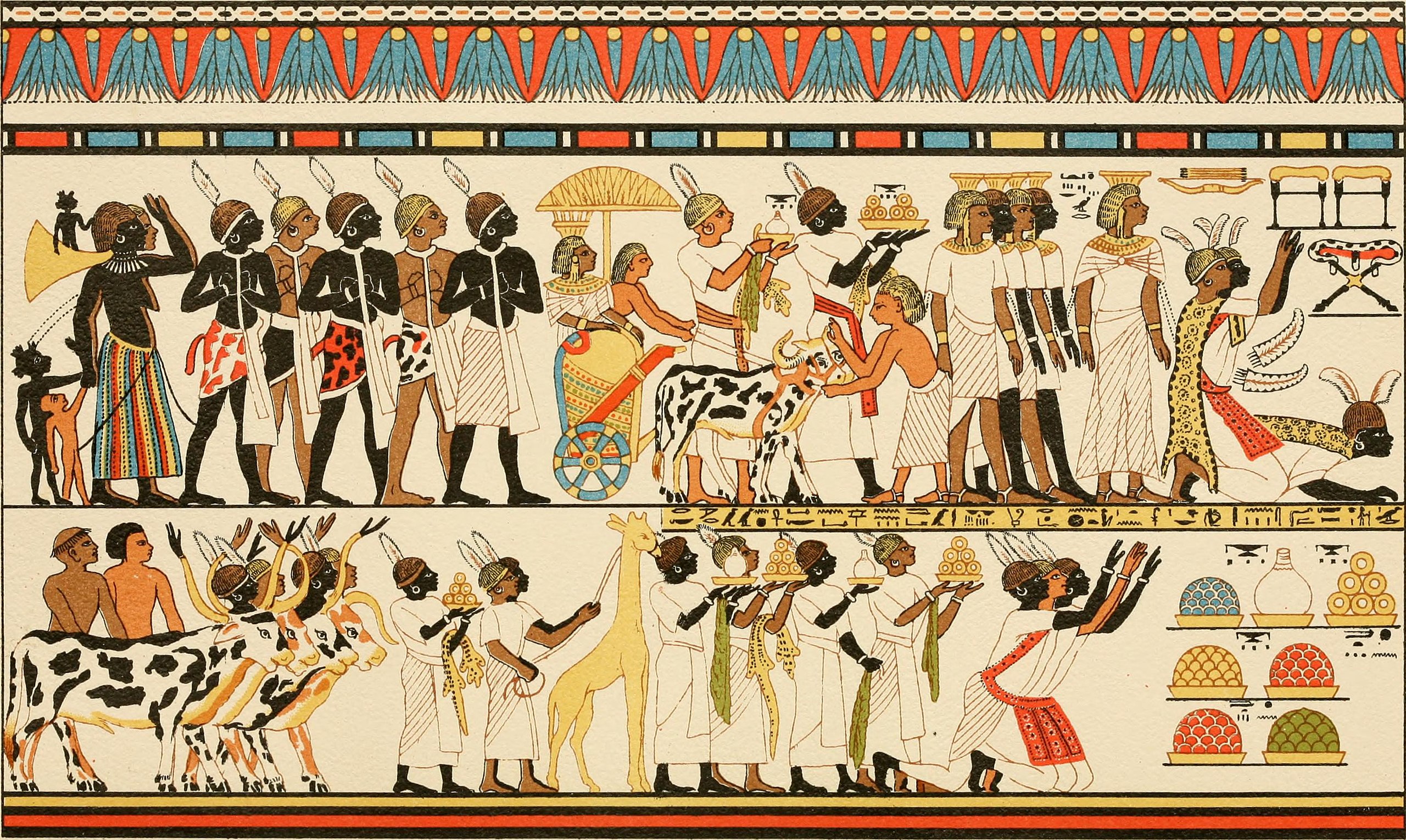

The descriptions orated within the papryological texts Instructions of Ani and Instructions for King Merikare provide insight into how Egyptians perceived themselves and others. In particular, an excerpt from Instructions of Ani says, “One teaches the Nubian to speak Egyptian, The Syrian and other strangers too. Say: “I shall do like all the beasts,” Listen and learn what they do.” This is a direct example of mimicry. Mimicry is seen as an opportunistic pattern of behavior: one copies the person in power, because one hopes to have access to that same power oneself (Singh, 2017). The Syrians and Nubians did this to assimilate more readily into the notion of being “ethnically” Egyptian. It is crucial to pay attention to how this expert uses the word “beasts” since it implies a more powerful, superior being, which is key to the idea of mimicry.

The preceding evidence demonstrates that ethnicity in ancient Egypt included linguistic, geographical, and racial identities in addition to culture and customs. Afrocentricity was a significant market for ethnicity in Egypt, and an Egyptian’s African or Black identity is what first defined them as a people. As we learn more about the intersections between their black identity and gender, specifically womanhood, it will be essential to keep this in mind.

Womanhood in Ancient Egypt

Although Ancient Egypt was a patriarchal society, women were seen as liberated, active, and occasionally unequal. Depending on what time period we examine them in, the perception of women in Ancient Egypt varies. For instance, women were viewed as independent throughout the Old Kingdom. Women were observed working in trade with males, unrestricted to the house (Graves-Brown, 2010). On the other hand, if we examine how women are treated in the Middle Kingdom, we may observe how the patriarchal system becomes observable. Women were occasionally viewed as the property of men. The status of the woman, including whether she was affluent or poor, also affected how severe the patriarchy was (Graves-Brown, 2010). In ancient Egypt, a woman was valued most favorably if she was a wife or mother. Being a wife or mother was considered to be one of the most important roles since it represented womanhood, adulthood, and respect for tradition. The Instructions for Ani give advice on how and when to be married as well as what a wife’s place is in her husband’s life. According to the Instructions of Ani, a papyrological text that serves as a doctrine for life, having a wife was crucial to a woman’s position in ancient Egypt (Graves-Brown, 2010).

The Instruction of Ani advises:

Take a wife while you’re young,

That she may bear a son for you;

She should bear for you while you’re youthful,

It is proper to make many people.

Happy the man whose people are many,

He is saluted on account of his progeny.

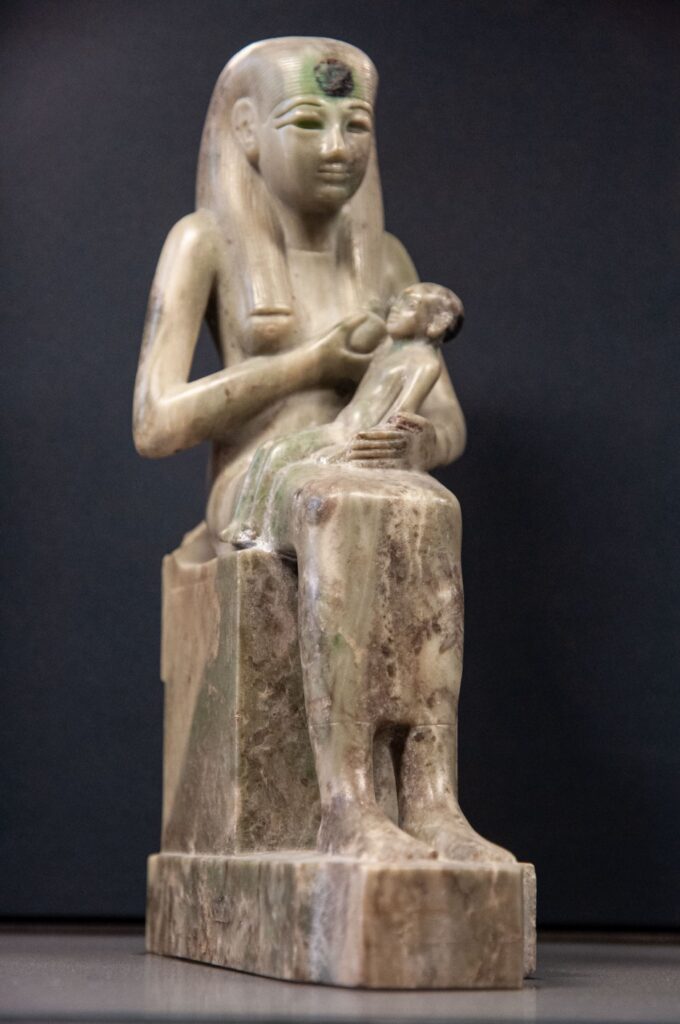

Statuette of Isis. Louvre, Paris.

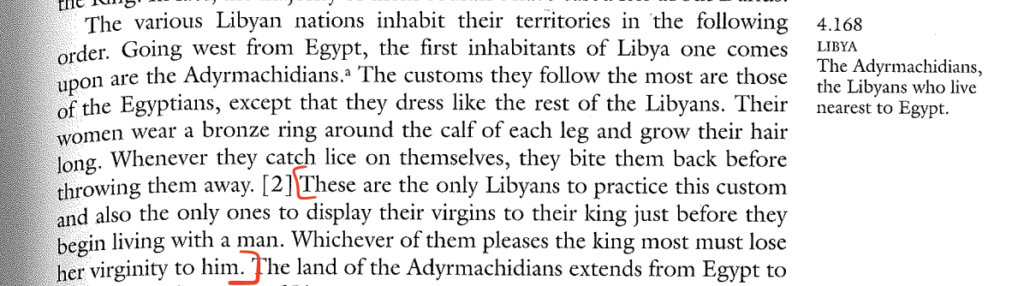

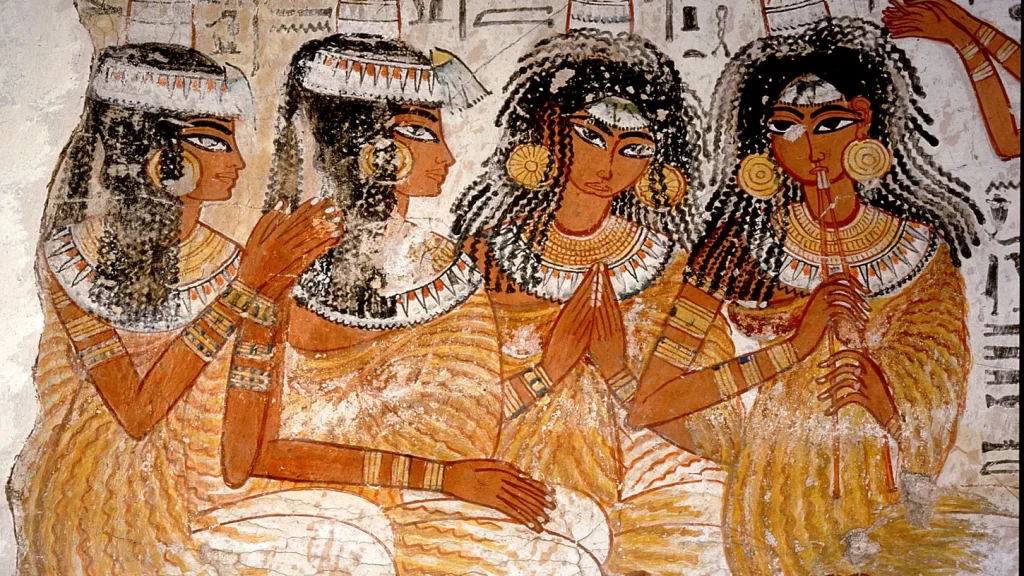

An Egyptian Woman’s Sexual Agency

The sexuality of a woman is another facet of womanhood. The sexuality of an Egyptian lady was highly valued and regarded as a means of empowerment and independence. Men were sometimes rewarded for the sexual favors they could give to women, while sometimes women were held responsible for the sexual weakness of men. While not strictly about Egyptian women, the ways in which the sexuality and womanhood of Libyan women are construed by the ancient sources is nevertheless of interest. In Book Four of Herodotus, Herodotus gives us examples of several women, of various ethnicities, and their conceptions of sexuality in accordance with their ethnicity. Libyan women engage in a custom described by Herodotus when they are preparing for marriage (photo to the right). No other tribe or race, but solely Libyan women, took this custom seriously. Many practices, including this one, can be attributed to the relationship between gender and ethnicity in ancient Africa, especially as reconstructed by those, like Herodotus, who were outsiders looking into these societies.

More Examples of African Women’s Sexual Agency

Blackness and Afrocentrism in The Ancient World

The average Egyptian lady is neither the beginning nor the end of ethnicity and gender. Even the Egyptian goddess Athena has been challenged about her racial background. Despite the fact that Athena was a Greek goddess, we can examine her from the perspective of women throughout the Ancient world. Additionally, Egypt and Greece had many similarities in terms of their respective gods; the Greek historian Herodotus even claimed that the Greeks received their gods from the Egyptians. In modern scholarship, there has been a tendency to take such statements and apply a racial lens to them, particularly in the readings about Black Apollo, by Patrice Rankin, and Black Athena, by Martin Bernal. When reading Rankin and Denise McCoskey’s thoughts on Black Athena and Black Apollo, there seemed to be an avoidance of saying Egypt was in fact an African nation and that Athena was black (Bernal). Bernal noted that maybe the term “African Athena” would have been better suited, but it still doesn’t change the fact that being African and blackness are intertwined. Bernal’s excuse for not calling the text African Athena was because his publicists at the time said, “Blacks no longer sell. Women no longer sell. But black women still sell!” This language and attitude towards the black body can be seen as insulting and reduces Black Women, especially those of the Ancient World, to just a mere selling point, instead of facing the fact that there is a persistent issue of race, identity, and their intersection that is very important when studying the Ancient World.

The racial background of Cleopatra VII, the final Egyptian queen, was likewise in doubt. Due to her family history and ancestry, some Classics scholars assume she was racially of Black and African blood. What would change, one would wonder, if these notable ladies from ancient history had been of Black and of African descent? Would people regard them less favorably? Black women are one of the most marginalized groups in society today, as is well known, simply because of their intersectionality. If this were accurate, there would be many parallels between the ancient world and the modern one. However, even the most basic inquiry into the racial and ethnic backgrounds of these Women raises significant information about the need to further the conversation about intersectionality in ancient civilizations.

Final Thoughts…

In Ancient Egypt and the Ancient World, ethnicity and gender intertwine in a complex yet well-known way. Where such intersectionalities begin and end have been analyzed and examined in this study, notably with regard to ancient Egyptian women. According to the evidence presented above, it can be stated that a woman’s sexuality was the main area where ethnicity and gender intersecting was present. Therefore, it reveals to us that, depending on how much these intersections of your identity affect the typical woman, a woman’s sexuality in Ancient Egypt was both admired and feared. It is encouraged to look into more intersectionality-related scholarship, particularly in relation to other issues like classism, elitism, sexism, and other topics.

References

Diop, C. A., & Selections. Diop, Cheikh Anta./Nations nègres et culture. English. (1974). The African origin of civilization: Myth or reality. translated from the French by Mercer Cook. Lawrence Hill & Co Publishers Inc.

Graves-Brown, C. (2010). Dancing for hathor: Women in ancient egypt. Continuum.

Kennedy, R. (2021, December 1). Talking about race and ethnicity in greco-roman antiquity. Talking about Race and Ethnicity in Greco-Roman Antiquity. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://rfkclassics.blogspot.com/2021/12/talking-about-race-and-ethnicity-in.html

Orrells, D., & Bhambra, G. K. (2011). African athena: New agendas. Oxford University Press.

Rogers, J. (2022, September). Ideology and Pharaohs—Ethnic Identity. Classics 220.

Singh, A. (2017, April). “Mimicry and Hybridity in Plain English.”