Colonial Impacts on Cultural Identity and Material Culture of Ancient Egypt

By Nate Ellis

Colonization can be defined as a process of establishing foreign control over target territories or peoples for the purpose of cultivation, often by establishing colonies and possibly settling colonial populations within them. Ptolemaic Egypt however is treated differently than the colonial expeditions of European dynasties such as the British Empire and is rarely analyzed under the connotation of colonial discrimination and domination. Instead, scholars understand Ptolemaic Egypt’s society and culture “as a set of impermeable communities/traditions coexisting with one another”(Neves 2020). This is true to an extent as Greco-Macedonian rulers adopted a method of balancing innovation and maintaining tradition native to the land and this resulted in a double faceted Greco-Egyptian society. The ‘Golden Age’ of Ptolemaic Egypt is said to be a result of the respect shown to the societies and civilizations that were present before the arrival of colonial powers. Due to how well these societies coexisted, many scholars are prone to ignore trends of discrimination and the impacts that colonization had on those native to Ancient Egypt. This piece attempts to showcase the manner in which social identities have been impacted along with the ways in which they adapted.

The Use of Papyri

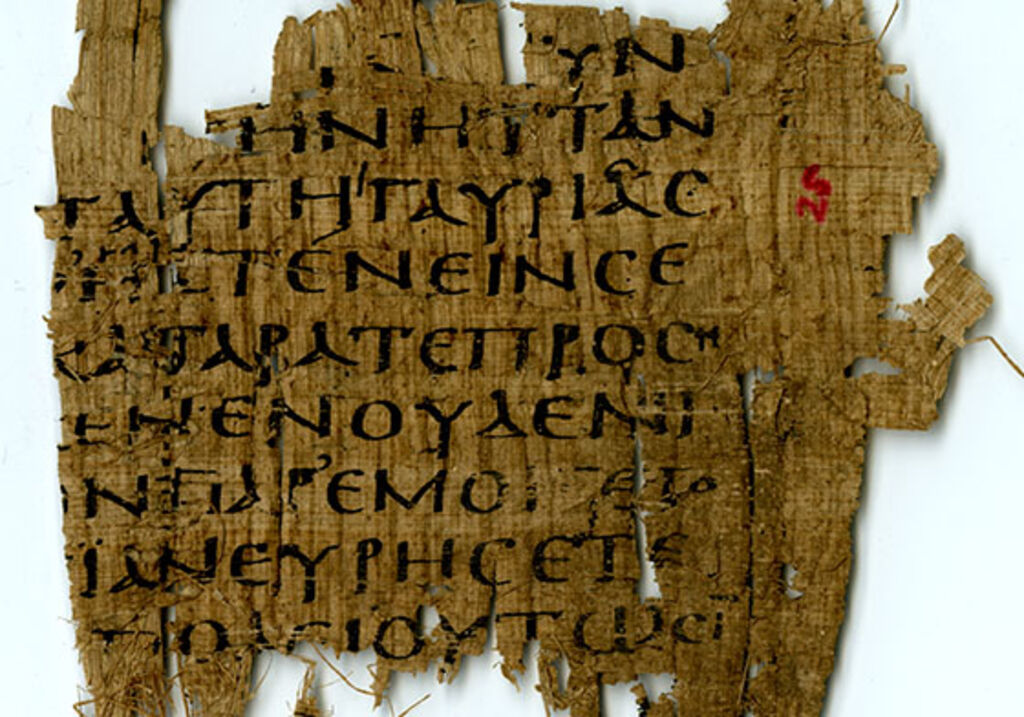

Eileen McCoskey, in her piece “Race Before ‘Whiteness’: Studying Identity in Ptolemaic Egypt”, condemns classical historians’ heavy reliance on papyri. Due to the colonial structure under which the majority of these texts were produced, Greek papyri provides us with a brief and one-sided view of history that causes historians to often view Egyptian identity as inferior or near nonexistent in the Ptolemaic time period. To avoid the consequences that come with relying so heavily on textual material, this piece seeks to incorporate the study of material culture in a field that is dominated by textual evidence.

Reconstructing the Ptolemaic Time Period

As scholars today attempt to reconstruct the Ptolemaic period, there is an emphasis placed on the fluidity of ethnic identity. Homi Bhabha’s “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse” delves into theories we can utilize in the study of colonial contact development in the Ancient African World. Bhabha’s theory of postcolonial hybridity is the most useful in analyzing this time period as it covers the mixing of two cultural forms and acknowledges the aspiration to hold a position of dominance over the colonized. The use of double-names (which is portrayed to be an attainable and common process among Egyptian natives) among government officials speaks to the claims of the fluidity of ethnic identity made by scholars. It is also understood that the majority of the Egyptian population aims to attain Hellenistic attributes(Hellene is one that is considered Greek) in hopes of upward social mobility and assimilation into the new colonial structure. Impacts of colonization on the people of Ancient Egypt’s social identity are reflected in their response to the political, economic, and social conditions of Ptolemaic Egypt.

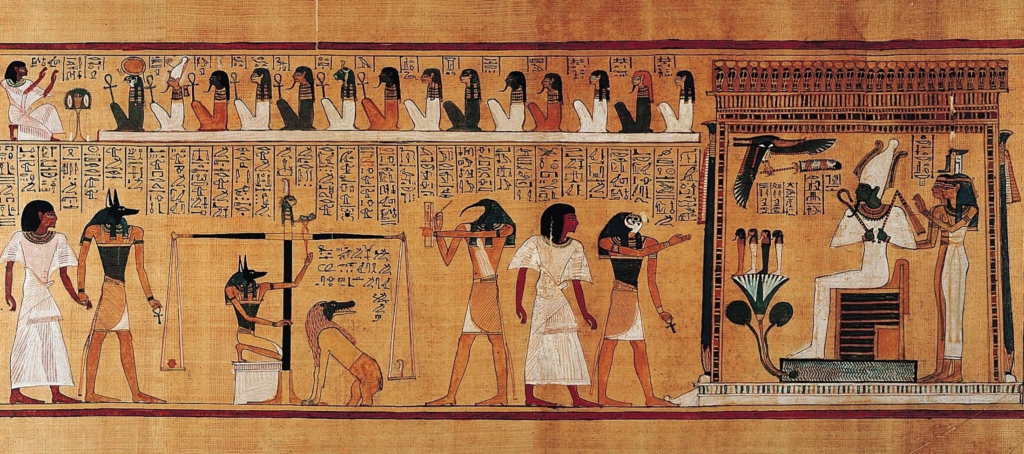

How we reconstruct the impacts of the colonizing powers rests not only on textual evidence but our access to material culture as well. The most obvious example of material evidence is the medium upon which text was written. Common media used for literary, religious and administrative texts includes limestone or ceramic pottery. Ancient Egyptian material culture has been the subject of extensive analysis as scholars often yield great amounts of evidence and information for the study of Ancient Egypt. Material evidence ranging from mummies and the skeletal remains of humans to carved and painted limestone contributes to our knowledge and understanding of the functionality, identities and social structures of this time period. The Ancient Egyptian civilization provided historians of the modern age with a unique opportunity to study the rare and significant material culture of their age. Majority of the art from Ancient Egypt served as representatives of spirits, powerful deities, kings and privileged officials. When this art is directly associated with Gods of worship they acted as intermediaries between the powerful deities and man. There is also an emphasis on the detail of the majority of these art pieces and how well they depict the deeper meanings behind them. The positioning of characters in statues or where they face on carved limestone can give us insight into their religion and lead us to new discoveries concerning their formal frontality.

The civilization of Ancient Egypt was not the only one with great cultural detail in their material evidence hence when they were acted upon or altered due to the influences of foreign civilizations, historians are able to make distinct observations on which civilization Ancient Egypt had encountered. Material objects subjected to the influence of foreign powers have given historians insight into which sects of the colonized society had been affected or reconstructed to fit the new colonial structure in place. As identity along with material culture tends to adapt to colonial rule, trends of Homi Bhabha’s ‘Hybridity’ begin to show. Due to the active role that material objects play in identity-construction as both identities begin to coexist, their material culture begins to adopt features from one another. Despite the merging of both material cultures, they also exist independently to a certain extent and scholars argue that the success of the colonizers’ consumables can be analyzed through the extent to which Greek features persist. This provides an estimate to the degree of hybridization of culture that has taken place. There is also an argument to be made that the adaptation of native features to the art of colonizers could be done solely for performative reasons.

The Cult of Serapis

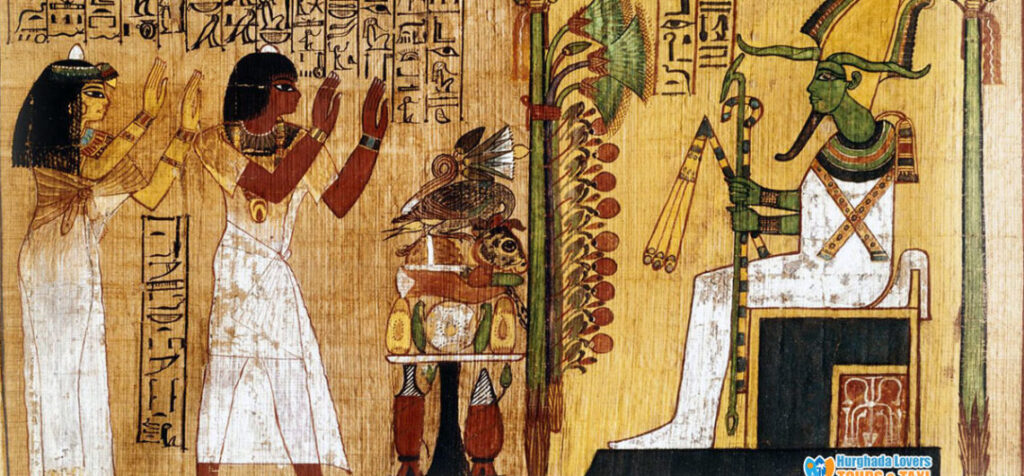

Colonial impacts on material culture are also visible in religious practices and the arrival of new gods. The Cult of Serapis is a prime example as to how new religions and beliefs form in this Greco-Egyptian society and how the features of each separate identity is incorporated.

In mythology, Serapis appears to man as a god that acts as a mediator between Greeks and Egyptians and many scholars argue that this representation of him speaks to the manner in which Ptolemy I wished for him to be interpreted. It is often argued that Serapis was created by Ptolemy I as a device to unite the Egyptian and Hellenistic population on the ground of religion. In depictions of Serapis his hair and beard are curly and unkempt similar to that of Greek gods like Zeus and Poseidon and directly contrasting trends of Egyptian art. The addition of a modius, a type of flat-topped cylindrical headdress or crown found in ancient Egyptian art, or a calathus, a basket in the form of a top hat, was meant to be representative of Egyptian culture.

The somewhat performative incorporation of Egyptian culture was intended to draw them towards the new religion but evidence suggests that they were rather uninterested. “The lack of temples built to Serapis by the Egyptians in the Ptolemaic period is evidence for the disinterest in the god ”(Murphy 2021). The Cult of Serapis seemed to appeal more towards the Greek identifying people, those who had become Hellenised and ambitious Egyptians who sought to further assimilate into the new social structure. Despite the reservations held by Egyptians towards Serapis, he never existed as a God solely to Greeks. He possessed attributes that were foreign to both sides of the colonial interaction and “was a Greek god to the Egyptians and an Egyptian god to the Greeks and Romans” (Murphy 2021).

The Greco-Egyptian civilization gives us insight into a unique colonial interaction where both identities attempted to coexist but did not function without Greek features imposing upon the latters’ identity, social structure and material culture. Scholarship on this time period often faces much contention, whether it be related to morality issues or problems of accuracy. Rebuilding this time period however, will always be a daunting task but the knowledge and perspective gained from persistent research has led to us being able to envision life in the Ptolemaic period.

References

Murphy, Lauren. “Beware Greeks Bearing Gods: Serapis as a Cross-Cultural Deity.” (2021)

Ikram, Salima. “Interpreting Ancient Egyptian Material Culture.” A companion to ancient Egyptian art (2014): 175-188.

Gillespie, Hope Elizabeth. “Imperialism, Identity, and Image: Looking at Colonial Objects in English Museums.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, September 11 (2020): 2.

REID, JOHN, and MATTHEW ROUT. “Social identity responses to colonisation.”

McCoskey, D. E. 2002. “Race Before ‘Whiteness’: Studying Identity in Ptolemaic Egypt”. Critical Sociology, 28(1-2), 13-39.

Bhabha, Homi. “Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse.” October 28 (1984): 125-133.