By Helen Banta

Many who imagine historical, especially ancient, periods of history will dull their vision. Everything will be less colorful and bright: the clothing is all white or off-white tunics that hang shapelessly and loosely off of the body. While ancient cultures typically do not appear to have complex tailoring techniques, their clothing was far from boring or bland. Clothing is central to life, whether we think about it or not. It is constant and identifying. Even today, the style of someone’s clothing can be informative about where they are from, their personality, or what they like. The Ancient Egyptians may not have worn the name of their favorite band across their chests or had a cap with the logo of their favorite sports team, but a lot can be learned about them and their identity by looking at what was closest to them – their clothing.

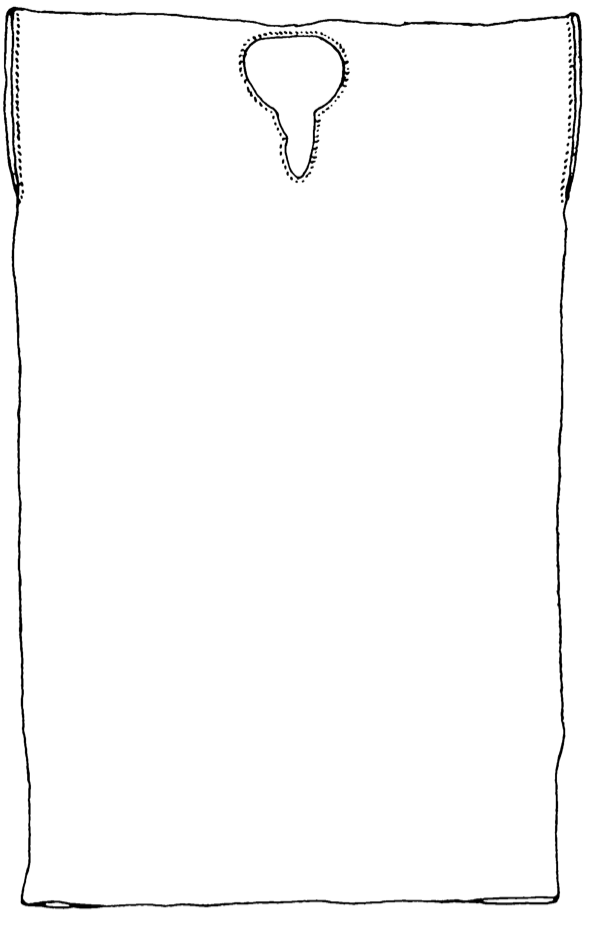

A 5th Dynasty (ca. 2500-2345 BCE) example of a representation of a tight v-necked shift and a men’s skirt (Riefstahl 1970, 254)

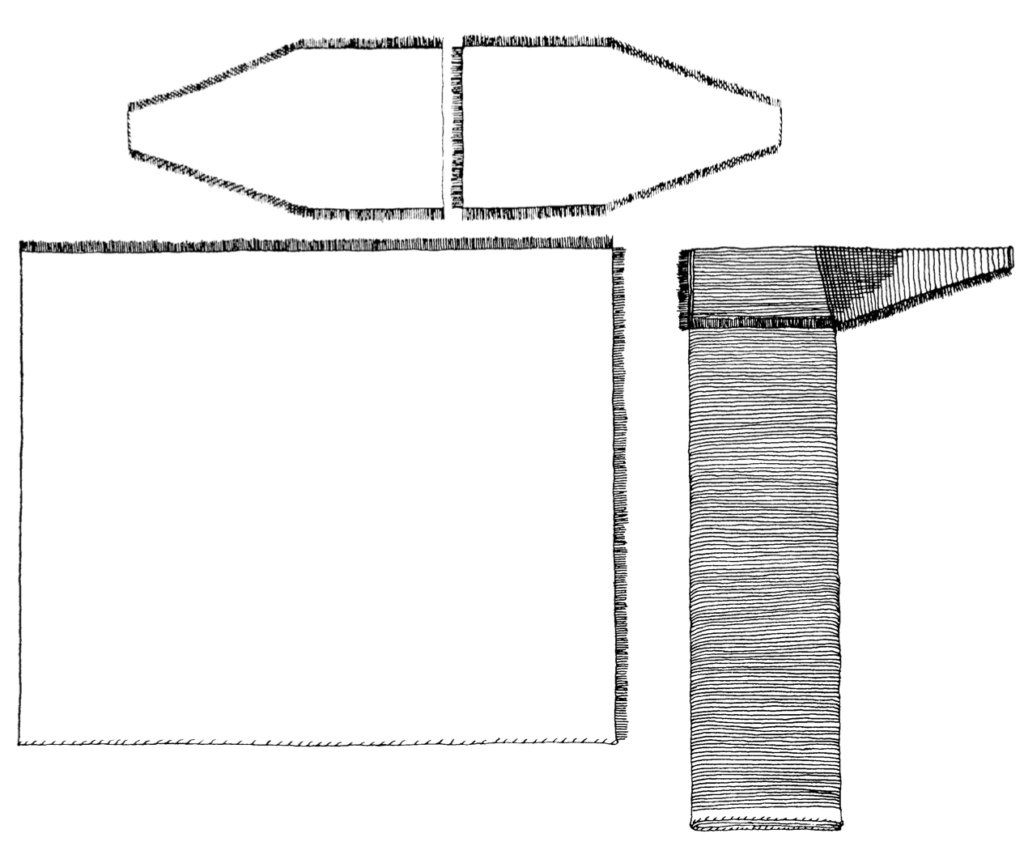

Much of the art from Dynastic Egypt contains similar types of clothing. For men much of the clothing is a skirt that often looks tied (either with itself or with an additional piece or girdle), tucked, or pinned at the waist to hold it up. There are also examples of the front part of this skirt being triangular and standing out away from the body. For women, many of the garments appear to be tight sheaths that begin, often, below the bust and are tight-fitting down to the ankle. Some have shoulder straps that form a V-shaped neckline, though given the nature of this dress it would be difficult to move in and so there are suggestions of it being artistic liberty or idealism that leads to it being so tight (Riefstahl 1970, 246, 256). There are also examples of bag tunics, which appears to be a large rectangle that is sewn up most of the way at the sides, leaving room for the arms, and has a hole cut for the neckline. This hole at the neck is shaped much like that of a modern polo shirt but without the collar. It has a rounder base that will sit around the neck when worn and an additional slit/opening that allows for there to be enough room to put on and take off the garment.

Diagram of a standard bag tunic (Riefstahl 1970, 254)

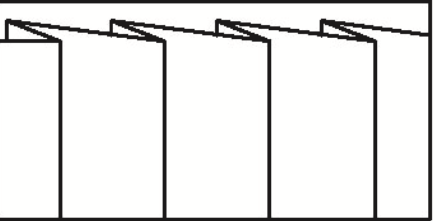

Additionally, there are depictions of pleats, including on dresses, sleeves, and kilts. The three primary types of pleats include vertical pleats, which create vertical lines on the body when worn—much like the majority of pleats in modern clothing—horizontal pleats, which create horizontal lines on the body when worn, and herringbone pleats, which is a combination of both horizontal and vertical pleats to create a more complex pattern. At first glance, some of these pleats could look like stripes on the fabric itself and not manipulation of the fabric, or even different manipulation of the fabric, such as gathering, but the additional volume of the garment, the way the lines fall, and extant garments do indicate that these designs were pleated (Riefstahl 1970, 248-9).

an example of a depiction of herringbone pleating on a men’s skirt (Riefstahl 1970, 250)

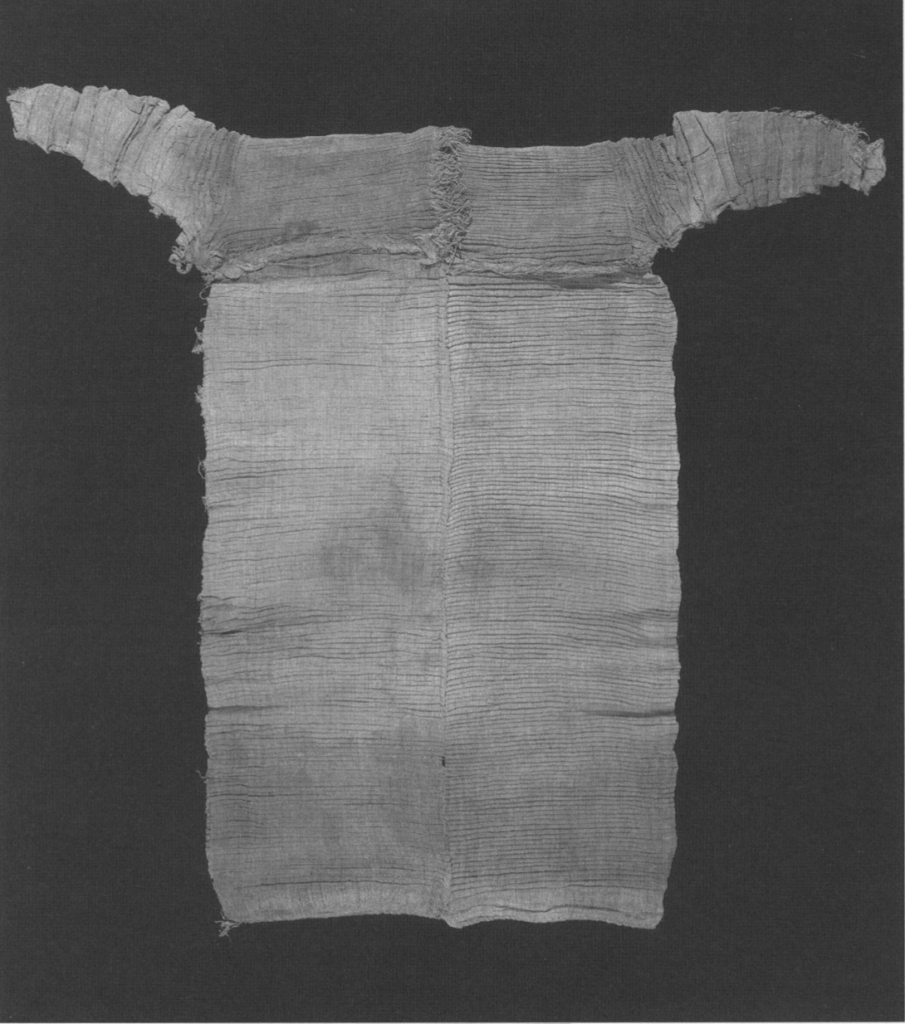

While Egypt does provide a good environment for preservation, there is not a multitude of extant clothing that has survived the past several thousand years. A couple of really interesting examples of clothing that includes pleats are horizontally pleated dresses, some of which came from a burial at Naga-ed-Dêr in Middle Egypt that is dated to roughly the First Intermediate Period (Riefstahl 1970, 245). Like much of the extant clothing from Ancient Egypt, they are made from undyed linen. These dresses are entirely pleated and are not a bag tunic, which would have been constructed of one, or maybe two, pieces, but instead has three separate pieces. There is one large rectangle that creates the skirt and then two identical pieces that each form half of the yoke and a sleeve. None of these pieces appear to be cut out of a larger piece of fabric but instead are woven into shape, an impressive approach. This means that the edges would have all been selvage edges, which means that they fray far less easily than cut edges would, resulting in a garment that could withstand wear and laundering much better. The bottom of the dress is not left raw but instead is finished with a rolled hem, where a small amount of fabric is turned up and then turned up again so that the raw edge of the fabric is hidden. This method is still frequently used in clothing construction to the extent that there are special attachments for sewing machines to make the process easier. These dresses are described as “clumsy” (Riefstahl 1970, 249) and as being made with “coarse” linen and stitching (Riefstahl 1970, 247). The side seam does definitively include a selvage edge as well as a fringe on the inside. Fringe is also seen on one side of the neckline and on the outside of the underarm seam (Jones 2014, 214-15). This fringe is discussed as being a trim, separate from the fabric, but most modern and ancient fabric has a fringed edge at the selvage, so this may just be a decorative use of the selvage. The shaping of the yoke is reminiscent of much of the other clothing in artwork, with it creating a deep V-neckline, here in the front and the back as the two pieces of the yoke do not appear to be connected to each other, and also placing the beginning of the skirt right under the bust. It is notably different from a lot of art because it is so heavily pleated, has long sleeves, and does not appear as though it would have been nearly as tight fitting.

Despite this proclaimed quality of the fabric and stitching, the pleats are incredible. They are fairly regular, with some irregularities around where the yoke moves from the shoulders to the arms and again as the wrists are approached, including some moments that begin to look vaguely like herringbone pleating. This is of course entirely understandable as there are many sharp curves of the body at the shoulders as well as a lot of movement that will crease the fabric in unintended ways. There is also an example of a similar dress from the Sixth Dynasty, which has pleats on the sleeves that are vertical instead of horizontal that eliminates some of these irregularities (Hall 1984, 136-8).

An example of a dress from the 6th Dynasty (ca. 2345-2181 BCE) with pleating that continues from the neckline down the sleeves, resulting in vertically pleated sleeves (Hall 1984, 140)

Linen is notorious for being a fabric that is easily wrinkled. This is reflected in many garments, such as one of these four dresses that shows some creases that are clearly from wear. However, this also means that it holds creases purposefully put in the garment very well, such as the pleats that survived wear during the day and thousands of years entombed. These designs are aided by the fiber content of the fabric that the Egyptians used, though it is unlikely that the fabric was chosen for this trait, as most clothing appears to have been made of Linen. Not only was linen widely available to the Egyptians due to their cultivating it in the Nile Delta and River Valley, but it is also a very breathable fabric that keeps the wearer cool in hot weather. Pleated garments also require far more fabric than an un-pleated bag tunic, indicating that this society and these specific people had the resources to use on the additional fabric, as well as the increased labor required to make these garments.

There are a variety of suggestions as to how these pleats were done. Some claim that, due to how fine and regular the pleats are, “a mechanical means must have been employed to produce them” (Riefstahl 1970, 249) and that this mechanical tool could be a corrugated wooden board that, according to this theory, would have been used like a gauffering iron is used today. Some of the people who support this theory also claim that a “fixative must have been used to give the pleats their permanency” (Riefstahl 1970, 249). While it is unsurprising that the undisturbed garments would remain pleated, this theory does a good job of explaining how the pleats could be so regular and last through daily wear. This is especially true of horizontal pleats that are very susceptible to gravity, and herringbone pleats that have more layers of fabric folded making them less secure. There is some evidence of a fixative being found on some extant clothing. A study that was conducted to figure out how some examples of fine linen with intricate pleating patterns “had retained their pleats for 4000 years,” found that while some of the fabrics had embalming mixtures on them, there were traces of tannins and humic substances present on 7 of the examples that appear to have come from a processing treatment, which they suggest was “retting the flax plants in slow-moving water” (Poulin 2022). Additionally, all of the examples had traces of starch and plant gum, which could have worked to reinforce the pleats (Poulin 2022). This suggests that they were treating their fabric, which could potentially help to hold the front of some men’s skirts out in front of them as some artwork depicts as well as reinforce pleats. The presence of embalming fluids also indicates the reuse of fabrics, which is logical due to the fabric’s value not only from the raw materials but the labor that went into producing it. This process, again, adds to the labor of the garments which highlights the fact that this society had the time and resources to care about their clothing.

Using experimental archaeology, Janet Johnstone investigated whether the pleats could have conceivably been produced by hand as opposed to mechanically. In addition, she also completed a couple of attempts testing a few techniques for starching the material using flax seed of different sizes. She pleated the material when it was damp and used her fingertips and fingernails to create the sharp edge of the pleats, as well as hammering them with a wooden bat. She also found that her pleats stayed without starching being necessary, but that the starch did stiffen the material and was helpful. Most importantly, she found that it is entirely feasible that the pleats were produced without mechanical assistance (Johnstone 2015, 83, 87). Whether or not these pleats were pressed at all is uncertain as there is not much information available, only brief unsubstantiated references (Mazow 2013, 220; Jones 2014, 224).

This combination of information seems to suggest that the dresses were hand-pleated by practiced craftspeople—potentially the same people who washed the garments—and were likely stiffened by some form of starch to help the pleats stay in place. Additionally, creases created by wearing could have come out when the fabric was wet in the laundering process, and Johnstone found that the creases could be lessened without washing by slightly wetting the dress and allowing it to hang overnight (Johnstone 2015, 87), though there is no clear indication or discussion of if the Ancient Egyptians did this. There are examples of the pleats being secured at the side seams, which would hold them in one spot, which would assist the re-pleating process (Jones 2014, 216).

Johnstone also found that by folding her material in half and pleating the layers together the pleating was faster, but did result in a crease down the center and a switch in the directionality of the pleats (Johnstone 2015, 80). This exact pattern is also seen on some of the extant examples of pleated dressed from Egypt. This is of course based only on my observation of the images, and while Jana Jones notes that “One half of the horizontal pleats opened upward and the other half opened downward” (Jones 2014, 215) it is unclear if those halves are the front and back of the garment or the left and right of the crease she notes at the center front, because in the accompanying image all of the visible pleats seem to open the same direction. There are examples, such as the previously mentioned 6th Dynasty dress that do clearly open in opposite directions (Hall 1984, 138). Regardless, this is a way that could have sped up the pleating process, which makes it all the more possible that a skilled craftsperson who pleats things often, could quickly create regular pleats.

Pleated dress from 6th Dynasty that Jones is referring to (Jones 2014, 215)

Despite all of this work pleating, which can be considered as an early form of tailoring, the dresses still remain fairly formless. It is inarguably heavily decorated, at least by means of fabric manipulation, and has a great deal of visual interest, but it is not tight fitting like many dresses in art nor heavily shaped in the way that many modern tailored garments are. There is debate as to how long these dresses were fashionable, as they are not commonly seen in artwork. Artwork of course may not have been depicting reality exactly, as addressed previously with the tight dresses. Realistic depictions in Egyptian iconography are also questionable because many bag-tunics appear in artwork to be made of fine and sheer linen while extant examples are made of a heavier and bulky weave (Riefstahl 1970, 254). However, the artwork does contain depictions of elements that are also found in these dresses, such as pleated sleeves. It would also make sense for these garments to have been in fashion for a short period of time as they are described as “clumsy and very ugly” (Riefstahl 1970, 248) by modern scholars and consume a great deal of resources. The style is not often found on monuments and is from humble burials, indicating, perhaps, a local fashion in Middle Egypt, possibly because of the colder winters (Hall 1984, 139). Others argue that there are references and depictions of pleated dresses found on stelae as well as a number of reliefs and figurines, alongside mentions in a Second Dynasty (ca. 2980-2686 BCE) linen list (Jones 2014, 230). Regardless of how widespread this style of dress was, pleats are widely depicted and are recognizably Egyptian, as Greek art depicts pleats but not in the same styles.

Ann Richards also suggests that some of the fabric depicted in art was pleated in an entirely different manner, where the fabric seems to almost pleat itself. She claims that this is what is represented by wavy lines on the clothing in the artwork, and can be seen in some extant garments. She believes that this happened due to the way that the fabric was woven and the manipulation of the way that the thread was spun and the spacing of the warp threads to create a texture similar to that a modern crepon fabric (Richards 2015, 139-40). This, as well as variations on common knife pleats, are still often found in modern clothing (such as pleated uniform or tennis skirts), but accordion pleats are less common, though they had a variety of uses throughout more recent historcal periods (such as the 18th Century in Europe)

Wall painting interpreted by Richards as depictions of natural pleats (Richards 2015, 141)

Pleats themselves are not unique to Egypt but appear across the world and time, including today. Nevertheless, these dresses, and pleated garments in general, provide a very interesting insight into the textile and clothing industries in general. These pleats likely would have come out and needed re-pleating when the garments were washed, suggesting that some people were willing to take the time to re-pleat their clothing or even to employ someone else to do it. Likely the same people who washed the clothing would be re-pleating the garments, but it is a skill that requires practice, especially for the quality of pleats that are depicted. Due to the effort required it would have likely taken a good amount of time and money to maintain these garments, which indicates the value placed on what people are wearing. Corroborating this value judgment is them being found in a tomb, presumably so that the owner could have them in the afterlife. Clothing is important across cultures and is something that tends to become more complicated when societies are more stabilized. For once you fairly reliably have food and shelter and an organized society, clothing is an obvious method of self-expression. It is close to the body, immediately noticeable, and can identify you as one of a group or an outsider. It is a clear and simple expression of identity.

Works Cited

Hall, Rosalind, and Lidia Pedrini. “A Pleated Linen Dress from a Sixth Dynasty Tomb at Gebelein Now in the Museo Egizio, Turin.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 70 (1984): 136–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3821584.

Johnstone, Janet M., Ashley Cooke, Pearce Paul Creasman, Salima Ikram, Geoffrey Killen, Marquardt Lund, Ann Richards, Alice Stevenson, and Denys A. Stocks. “PRACTICAL DRESSMAKING FOR ANCIENT EGYPTIANS – MAKING AND PLEATING REPLICA ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CLOTHING.” In Egyptology in the Present: Experiential and Experimental Methods in Archaeology, edited by Carolyn Graves-Brown and Wendy Goodridge, 75–90. Classical Press of Wales, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvvnbgg.9.

JONES, JANA. “THE ENIGMA OF THE PLEATED DRESS: NEW INSIGHTS FROM EARLY DYNASTIC HELWAN RELIEFS.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 100 (2014): 209–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24644971.

Mazow, Laura B. “Throwing the Baby Out with the Bathwater: Innovations in Mediterranean Textile Production at the End of the 2nd/Beginning of the 1st Millennium BCE.” In Textile Production and Consumption in the Ancient Near East: Archaeology, Epigraphy, Iconography, edited by M.-L. Nosch, H. Koefoed, and E. Andersson Strand, 12:215–23. Oxbow Books, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dvx0.15.

Poulin, Jennifer, Paulocik Chris, Veall Margaret-Ashley. “Found in the Folds: A Rediscovery of Ancient Egyptian Pleated Textiles and the Analysis of Carbohydrate Coatings.” Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 27,13 4103. 25 Jun. 2022, doi:10.3390/molecules27134103.

Richards, Ann, Ashley Cooke, Pearce Paul Creasman, Salima Ikram, Janet M. Johnstone, Geoffrey Killen, Marquardt Lund, Alice Stevenson, and Denys A. Stocks. “DID ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEXTILES PLEAT THEMSELVES?” In Egyptology in the Present: Experiential and Experimental Methods in Archaeology, edited by Carolyn Graves-Brown and Wendy Goodridge, 139–50. Classical Press of Wales, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvvnbgg.12.

Riefstahl, Elizabeth. “A Note on Ancient Fashions: Four Early Egyptian Dresses in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.” Boston Museum Bulletin 68, no. 354 (1970): 244–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4171540.

Strand, Eva Andersson. “The Basics of Textile Tools and Textile Technology: From Fibre to Fabric.” In Textile Terminologies in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean from the Third to the First Millennnia BC, edited by C. Michel and M.-L. Nosch, 8:10–22. Oxbow Books, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cfr985.6.